Gene transcription is the process by which DNA is copied and synthesized as messenger RNA (mRNA) — which delivers its genetic blueprints to the cell’s protein-making machinery.

Now researchers at MIT and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) have identified a hidden, ephemeral phenomenon in cells that may play a major role in jump-starting mRNA production and regulating gene transcription.

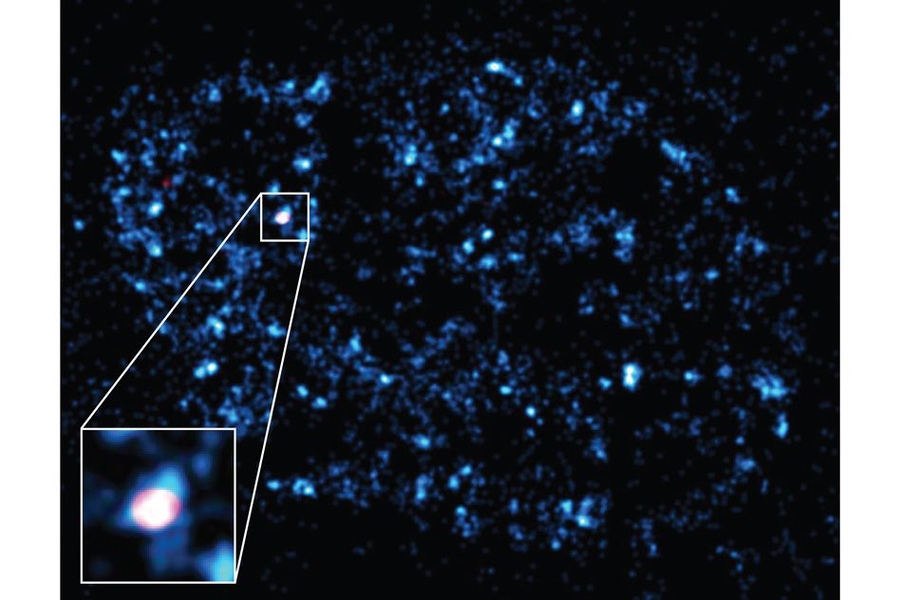

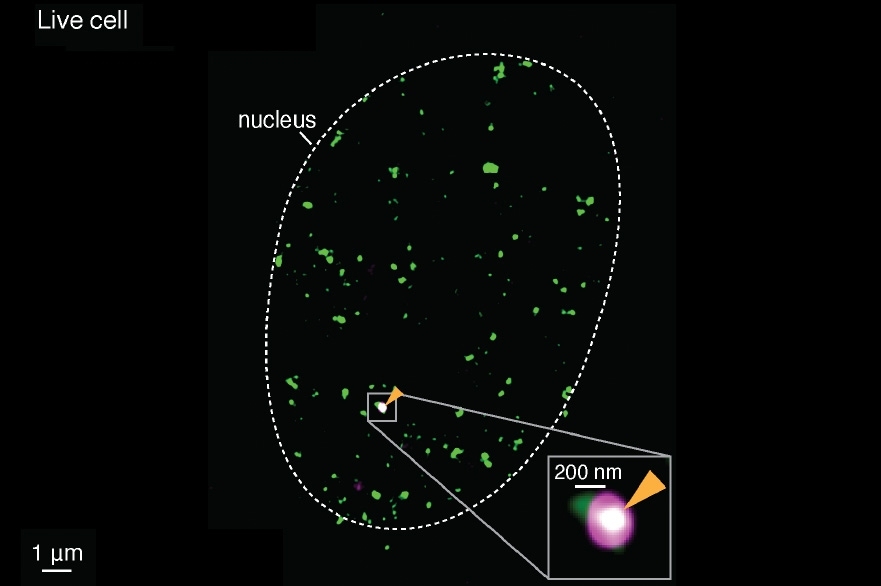

In a paper published in the online journal eLife, the researchers report using a new super-resolution imaging technique they’ve developed, to see individual mRNA molecules coming out of a gene in a live cell. Using this same technique, they observed that, just before mRNA’s appearance, the enzyme RNA polymerase II (Pol II) gathers in clusters on the same gene for just a few brief seconds before scattering apart.

When the researchers manipulated the enzyme clusters in such a way that they stayed together for longer periods of time, they found that the gene produced correspondingly more molecules of mRNA. Clusters of Pol II therefore may play a central role in triggering mRNA production and controlling gene transcription.

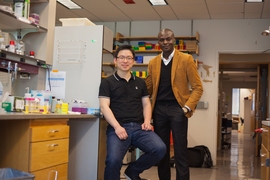

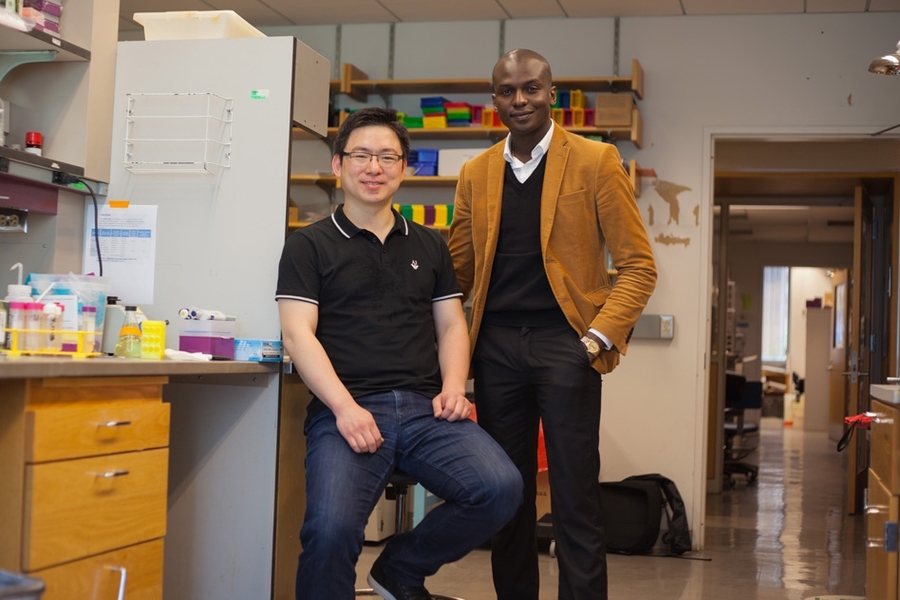

Ibrahim Cissé, assistant professor of physics at MIT, explains that because of their transient nature, enzyme clusters have largely been regarded as a mystery, and scientists have questioned whether such clustering is purposeful or merely coincidental. These new results, he says, suggest that, although short-lived, enzyme clustering can have a significant impact on major biological processes.

“We think these weak and transient clusters are a fundamental way for the cell to control gene expression,” says Cissé, who is senior author on the paper. “If a small mutation changes the cluster’s lifetime ever so slightly, that can also change the gene expression in a major way. It seems to be a very sensitive knob that the cell can tune.”

What’s more, Cissé says scientists can now explore Pol II clusters as targets to “stall or induce a burst of transcription” and control the expression of certain genes, to explore cancer drugs and other gene therapies.

The paper’s co-authors include Won-Ki Cho, lead author and postdoc in the Department of Physics; Namrata Jayanth and Jan-Henrik Spille, also postdocs in physics; Takuma Inoue and J. Owen Andrews, graduate students in physics; and William Conway, an undergraduate in physics and biology; as well as researchers from HHMI’s Janelia Research Campus: Brian English, Jonathan Grimm, Luke Lavis, and Timothée Lionnet who is also co-senior author with Cissé.

Imaging at super-resolution

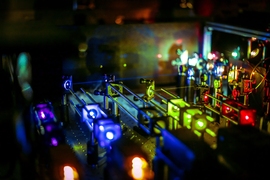

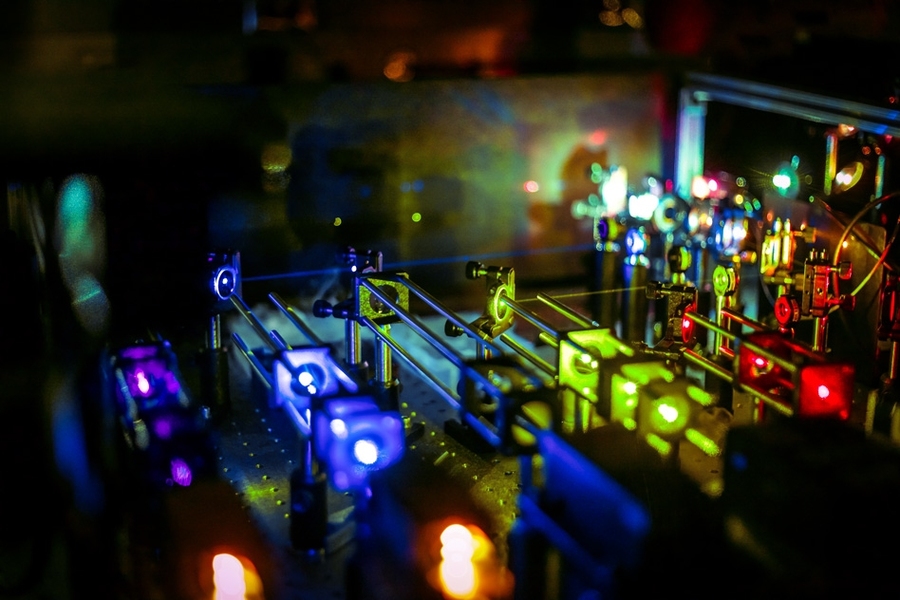

Pol II enzymes only cluster together for very short periods of time, on the order of several seconds. These clusters are also extremely small, on the scale of 100 nanometers in width. Because they are so tiny and fleeting, Pol II clusters and other weak and transient interactions have largely been hidden from view, essentially invisible to conventional imaging techniques.

To see these interactions, Cissé and his colleagues developed a super-resolution imaging technique to visualize cellular processes at the single-molecule level. The team’s technique builds on two existing super-resolution methods — photo-activation localization microscopy (PALM) and stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM). Both techniques involve tagging molecules of interest and lighting them up one by one to determine where each molecule is in space. Scientists can then merge every molecule’s position to create one super-resolution image of the cellular region.

While incredibly precise, these imaging techniques rely on the assumption that every molecule remains stationary. Molecules that come and go, and quickly cluster and scatter, are difficult to track. To catch Pol II clusters in action, Cissé and his team tweaked existing super-resolution imaging techniques, looking not just at a single enzyme’s position, but also at how frequently molecules were detected. The higher the frequency of detection, the higher the chance that a cluster has formed.

The team applied their technique to image cells, using a camera that recorded one frame every 50 milliseconds, running continuously for up to 10,000 frames.

A transient lifetime

They then created a cell line that included a bright fluorescent tag for mRNA, as well as a fluorescent tag of a different color for Pol II enzymes. The team applied its super-resolution technique to image a particular gene inside the cell, called beta-actin, which has been characterized extensively. In experiments with live cells, the researchers observed that, while previously transcribed mRNA molecules lit up on the gene, new Pol II clusters appeared on the same gene, for about 8 seconds, before disassembling.

From these experiments, the group was uncertain as to whether the clusters had any impact on mRNA production, since the time it takes from the start of transcription to the complete production of mRNA takes significantly longer — about 2.5 minutes. Could a cluster, appearing for just a fraction of that time, have any effect on mRNA?

To answer this question, the team stimulated the cells with a chemical cocktail which they knew would affect gene transcription and mRNA output. In these cells, they found that, just before the mRNA peak appeared, clusters formed on the gene and actually remained stable for as long as 24 seconds — a fourfold increase in a cluster’s typical lifetime. What’s more, the number of mRNAs increased by a similar amount.

After repeating the experiment in 207 living cells, the team found that the lifetime of Pol II clusters was directly related to the number of mRNA produced from the same gene.

Cissé speculates that perhaps Pol II clusters acts as an efficient driver of gene transcription, speeding up an otherwise inefficient process.

“It makes sense that you wouldn’t want an efficient initiation process, because you don’t want to randomly turn on any gene just because there was a random collision,” Cissé says. “But you also want to have a way to change the initiation from an inefficient to an efficient process, for example when you want to express a gene in response to some environmental stimuli. We think that these transient clusters are probably the way that the cell can render transcription initiation efficient.”

Next, Cissé plans to follow up his studies on Pol II clusters to determine what are the forces holding them together, as well as how they’re formed, and whether other molecular factors cluster with similar effects.

“I suspect there are new biophysical phenomena that come from weak and transient interactions,” Cissé says. “This is an underexplored area in biology, and because the interactions are so elusive we understand very little about how the regulatory processes happen inside a living cell.”

This research was funded, in part, by the National Institutes of Health Director’s New Innovator Award to Cissé, and additional support from the National Cancer Institute, the MIT physics department start-up funds, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.