Each Friday morning this semester, the 24 students in MIT course 11.469 (Urban Sociology) have traveled one of two routes to class.

Half of them gather at 6:50 a.m. in Cambridge, Massachusetts, clamber into a rented van for an hour-long drive, and then make their way through a lengthy security screening. The other 12 take a short walk — from their cells.

The students convene in a room at the Massachusetts Correctional Institution at Norfolk (MCI-Norfolk), the largest medium-security prison in the state, where together they pass into another realm — one where the ideas of Max Weber, Émile Durkheim, and W.E.B. DuBois are discussed along with topics such as desegregating Boston public schools.

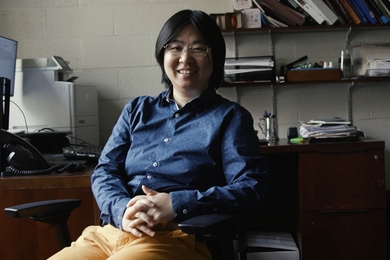

Conceived and taught by Justin Steil, assistant professor of law and urban planning in the MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning (DUSP), the course covers core foundational texts in urban sociology. But it’s also “an opportunity to create new knowledge about the drivers of urban inequality,” he says. “The wide range of experiences on both sides creates much more productive conversations about the nature of urban inequality and potential responses.”

The DUSP contingent is a mix of masters and doctoral students. Their classmates at MCI-Norfolk are enrolled in a bachelor’s degree program, earning credits from Boston University’s Metropolitan College.

The MCI-Norfolk students are a racially and economically diverse group, ranging in age from mid-20s to 60s. They are also serving a range of sentences. “Some get out in the next few years,” says Steil, “some are serving life without parole.”

“When you put such a diverse group of people together, and everyone has their own perspective, your interpretation and understanding of these texts is really different,” says doctoral student Aditi Mehta, the teaching assistant for the course. “So the idea that you have such different lived experiences to draw from is really powerful.”

To help bridge those divergent experiences on the first day (which, Mehta observes, is “always a little awkward in any class”), the teachers distributed 12 historic and contemporary photographs to pairs of MCI-Norfolk and MIT students, who analyzed and described the social processes they saw at work. “The idea was to recognize that everybody is bringing knowledge to the classroom, that we’d be working together and learning from each other,” says Steil.

That first class also introduced an idea that resonated deeply with the students: C. Wright Mills’s concept of the “sociological imagination.”

“The students keep coming back to this concept,” says Steil. “How do we think about our individual experiences in relation to collective experiences and history, and our place in it? What are the commonalities and variations in our experiences?”

One incarcerated student noted the multiple perspectives in the class that made possible new kinds of conversations about inequality, adding: “Two groups of strangers essentially came together from two different worlds and formed a classroom dynamic that cannot be repeated.”

For MIT and MCI-Norfolk students alike, it’s a demanding course, involving roughly 200 pages of theory-laden readings each week, weekly response papers, student-led presentations, a midterm reflection paper, and a final paper. Through discussions of the texts and various in-class group activities, the students have built a strong rapport.

Pairs of MIT and MCI-Norfolk students lead a conversation based on each week’s readings, often connecting them to their own lived experiences and current events. Doctoral student Laura Delgado and her project partner structured a debate based on readings about social capital and social networks, using as a case study the Metco Program, through which students in Boston public schools can attend schools in suburban neighborhoods.

Prisoners do not have Internet access, so project teams can’t rely on email or other digital communication tools to map out their strategy. Instead, students use the 15-minute break during each week’s class to plan their presentations.

“It was a really good learning experience, and nice to be able to develop it over the semester together,” says Delgado. “My project partner has been really proactive. We set up a reading schedule, a deliberate process to pace ourselves and have time to prepare.”

The course was made possible in part by a grant from MIT’s Priscilla King Gray Public Service Center, which enabled the DUSP students to travel to MCI-Norfolk in the rented van each week. It was an obvious fit with the PKG Center’s mission to help students work collaboratively with communities beyond campus.

“Justin’s proposal was an innovative approach to both enriching the education of MIT students and enhancing higher education opportunities for a typically overlooked population,” says Alison Hynd, director for programs and fellowship administrator at the PKG Center.

Several of the incarcerated students have expressed how the class has given them confidence as they prepare to reenter society and motivation to continue learning.

“One of the most memorable class sessions for me was one in which we participated in a debate,” one student from MCI-Norfolk wrote. “I had a grasp on the material and was able to defend it well. Receiving ‘well dones’ from my classmates, especially the MIT students, was a highlight. It proved to me that I had something to offer even amongst great minds.”

“The class has inspired me to work toward earning a master's degree,” wrote another, “when I am finally released.”

As for the MIT students, Steil says the course has motivated some to engage more deeply with prisoners’ issues going forward. “One of the students is very interested in the experiences of prisoners reentering society when they’re released,” he says. “For her final paper she is working on developing a map of stakeholders engaged in reentry issues and thinking about ways that students from the class in Norfolk, who are getting their bachelor’s degree in prison, could find opportunities to be part of research work afterward.”

“As a teacher, I feel incredibly lucky to be able to do this,” he says, “finding ways to bring MIT students beyond the Kendall Square neighborhood to be part of the metropolitan area we all live in, and teaching and learning with the broader communities to which we are connected.”