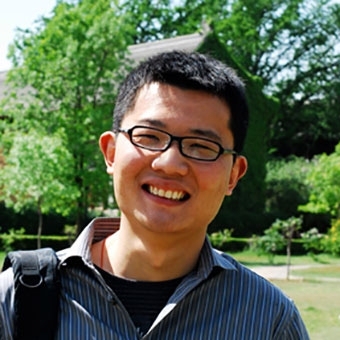

Yiqing Xu knows a lot about duality. He’s a Chinese citizen steeped in American higher education. He’s an economics student who was drawn to political science. And as a fifth-year doctoral student preparing to embark on his academic career, Xu plans to continue his research in two political science fields: methodology and Chinese political economy.

Xu studied economics as an undergraduate at Fudan University in Shanghai where he was born, and continued with economics in a master's program at the China Center for Economic Research at Peking University. His master's research, however, veered into the realm of political science. He was in a research team that collected data on 300 Chinese villages spanning 25 years to tease out the effects of democratization at the village level. The country introduced village-level elections in the 1980s.

“I'm really interested in the interaction between formal institutions like elections and informal institutions like lineage groups or temple institutions,” Xu says.

It became clear to Xu that politics plays an increasingly important role in determining China’s course, in both economics and social and political development. This led him to pursue a doctorate in political science at MIT. His research here included an extensive experimental study that involved sending letters to local officials in 2,000 Chinese counties.

However, not every situation lends itself to an experimental design. Xu delved into the finer points of time-series cross-sectional, or longitudinal, data analysis used to identify causal relationships among variables, and set about improving the tools. “I was originally doing comparative policy and I figured out a very interesting question in methodology and I started doing both,” he said.

Xu began working with the Synthetic Control method, which produces a more accurate control for a study subject than the traditional Difference-In-Differences method, which produces a sort of control group by averaging actual comparable subjects. For example, for a study of the effects of a policy change in a U.S. state, the Difference-In-Differences method averages data from the other states and uses the average state as a control for the state that was affected by the policy. The Synthetic Control method adjusts that data to produce a hypothetical state that is a closer analog to the state in question. Xu has developed a variation dubbed Generalized Synthetic Control that handles cases with multiple subjects and provides valid and more interpretable uncertainty estimates.

Improved methods of analyzing observational data are particularly important for studying China, which is opaque but critical to 21st-century global politics.

“We know fairly little about China,” Xu says. “Now we can more systematically collect data and analyze those issues in villages, in cities, to see how local government responds to citizens, and maybe, at a higher level, the logic of the elite politics. And how, for example, people's ideas change and for what reasons,” he says.

Xu’s dissertation, "Causal Inference with Time-Series Cross-Sectional Data with Applications to Chinese Political Economy," won The Society for Political Methodology’s John T. Williams Dissertation Prize for the best dissertation proposal in the area of political methodology in 2014. He expects to complete his doctorate in June 2016, and he’s already accepted a faculty position at the University of California at San Diego for the fall.

Xu will take with him a strong appreciation of the MIT culture. His academic experience includes research at Harvard University and a pre-doctoral fellowship at Stanford.

“What's special about MIT is the interaction between faculty members and graduate students,” he says. “I haven't seen another place that has that close relationship. The professors' doors are always open.”