On tour with Paul Simon in the late 1990s, musician Mark Stewart bought his first didgeridoo, a hollow wind instrument from Australia known for its sonorous quaver. Once home in New York, Stewart was walking in the Garment District when he noticed something. In a dumpster were the cardboard tubes, of all different sizes, used to hold bolts of fabric, echoing the familiar cylindrical shape of his new instrument.

“Every single tube was a column of air waiting to be played,” Stewart recalls. As he tells it, he clambered inside at once and began to assemble and play these tubes in an impromptu performance. He began to see the world as raw material, even its most quotidian shapes containing a wealth of sonic possibility. Everything, it appeared, was a potential didgeridoo.

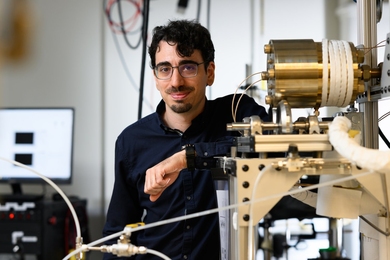

Sponsored by the MIT Center for Art, Science, & Technology (CAST) and MIT Music and Theater Arts, Stewart — a world-class multi-instrumentalist, singer, composer and instrument designer — will embark with the Glass Lab upon a new challenge: creating a small chamber orchestra out of glass. With Glass Lab Director Peter Houk, Stewart will head a yearlong workshop starting in late September to explore new sounds through the design of glass instruments — with an emphasis on the new and bizarre.

The partnership is a natural one. The Glass Lab is a place where “everything is worth exploring just because it’s an idea,” says Glass Lab instructor Martin Demaine, the Angelika and Barton Weller Artist-in-Residence in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. Built in the late 1960s as part of the Department of Materials Science and Engineering, the Glass Lab offers students the opportunity to observe first-hand the material principles learned in the classroom. The lab’s enormously popular non-credit workshops demonstrate that artistic production and academic study can be overlapping courses of exploration.

In this same spirit of playful inquiry, Stewart approaches the work of instrument building. Most of what he knows about the physics of sound making was learned through trial and error. Making sounds, he believes, is instinctual and needs no formal training. “The word 'musician' is too often used to discourage people from participating in their birth right as sound-makers,” Stewart says.

Like a tinker, he often carries with him a seemingly bottomless bag filled with his creations. On his first exploratory visit to the Glass Lab, Stewart rolled out a motley bunch of homemade instruments crafted from PVC pipes, bouncy balls and coat hangers. Everyone in the studio froze as a swell of new sounds emerged. With these appealing yet oddball instruments, Stewart hopes to incite untamed sound making through the power of sheer, unexpected sensorial delight.

In Stewart’s philosophy, each instrument holds a kind of cosmic purpose, possessing an intrinsic sonic quality that is theirs alone and our role as sound makers to bring forward. He speaks of sounds in evolutionary terms — as if they were living organisms, each with its own essential function fitting perfectly into the larger aural ecology. Some sounds, such as those of the versatile and ubiquitous piano, have found currency in their integration into bands and orchestras — which amount to the star makers of the sound world. Other sounds are unrealized or have wound up neglected in strange historical cul-de-sacs, doomed to near extinction. These are the sounds — the atypical, original, and unheard of — that interest Stewart the most.

At MIT, Stewart looks forward to collaborating with kindred spirits. Of the first meeting with Houk and others at the Glass Lab, he recalls, “There was this feeling, ‘Why don’t we just build everything?’ I felt light-headed with possibilities.” Stewart has never worked with glass before, and is anxious to discover what new kinds of instruments the material might yield.

“I’m most excited by something called the Prince Rupert Drop,” he says.

A common curiosity in glass blowing, the Prince Rupert Drop is a tadpole-shaped dollop formed by dripping molten glass into cold water. With the drop’s exterior cooling faster than its viscous center, a compressive outer shell is produced while the interior exists in a tensile state. The result is a teardrop of both incredible strength and vulnerability. While its body is immune to even a hammer’s strike, the Achilles heel of the Prince Rupert Drop is its slender, tapered tail. At the slightest pressure on the tail, the surface tension in the object is broken and the droplet shatters instantly, leaving behind a residue of powder-fine splinters.

What might this peculiar and paradoxical object contribute to the glass orchestra? The resulting instrument might be “a cross between a marimba and a glass harmonica and something new,” Stewart says.

Audiences will have to wait to find what vitreous inventions lie in store. The CAST spring concert on Friday, April 5, will present a preview of the glass orchestra before it is unveiled in full at MIT as part of the annual convocation of the Glass Art Society. Although much about the performance is to be revealed, Stewart is already imagining a spectacular coda: the popping sound of dozens of Prince Rupert Drops, one by one, exploding in the air. But that is only one possibility.

In a yearlong residency, the musician and instrument designer will build a glass orchestra with MIT students.

Publication Date:

Caption:

Musician and instrument designer Mark Stewart.

Credits:

<a href="http://www.kotekan.com" target="_blank">Christine Southworth</a>