When physics professor Ulrich J. Becker signed on an experiment to search for dark matter in space, he didn't know that the experience would involve climbing fences at Kennedy Space Center to escape an alligator while 20 guards with machine guns descended on him.

Becker gave a behind-the-scenes talk Jan. 24 on the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer's 1998 space shuttle shakedown cruise as part of IAP's physics lectures for the general MIT community, organized by physics professor Edward H. Farhi.

Although no one can see it, researchers suspect that dark matter makes up most of the universe. Anti-matter doesn't exist on Earth because it is annihilated when it reaches the atmosphere, so space-based detectors are the only answer.

The Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, a sophisticated cosmic ray detector, was born "one day as we sat in Building 44 and thought, 'How can we prove or disprove the prejudice that there is only matter?' One anti-carbon nucleus could change our whole perception of the universe," Becker said.

The result was a multi-nation collaboration, led by Nobel laureate Samuel Ting, Thomas Dudley Cabot Professor of Physics, which received relatively quick approval from NASA. That was the last painless part of the process.

In addition to seeing alligators and crocodiles in ditches around the space center complex (including the one that blocked his access to a parking lot in the high-security shuttle launch pad area), Becker gathered endless security badges, suffered through dozens of almost incomprehensible flow charts and fretted over six on-board computers that insisted on fighting with each other instead of doing their jobs.

He donned funny suits to work on the huge magnet while it was loaded in the shuttle's payload area, and found that he had to remove his wedding ring before entering the area because any foreign object in the shuttle could end up as space debris, whipping around with the velocity of a gunshot and endangering future space-walking astronauts.

Building the detector was fraught with challenges. It incorporated an incredibly powerful magnet, which could not interfere with the astronauts' life support systems. It had to withstand the shock of re-entry into the Earth's atmosphere, and it had to use little or no power. The scientific obstacles were overcome only to have logistical ones crop up.

AMS was assembled in Switzerland with the precision of a Swiss watch, but how do you a transport a monstrous magnet that might interfere with a airplane's electronics? And how do you get it through customs? Finally, Lufthansa agreed to fly it directly to Kennedy Space Center in Florida, avoiding customs by landing in diplomatically neutral territory.

Despite the trials and tribulations of the experiment, Becker is excited and mystified by the results: 100 million particles were detected (although not a single anti-carbon nucleus) with four times as many positrons as electrons showing up near the Earth's magnetic equator. These electrons and their antiparticles known as positrons are continuously produced by collisions among other high-energy cosmic particles. Scientists expected that equal numbers of electrons and positrons should be produced, and that the magnetic field would repel fewer energetic particles arriving around the equator. Becker hopes that the beefed-up detector, with a superconducting magnet, will provide more answers when it is installed on the International Space Station for a three-year stint in 2005.

Deborah Halber

Charm school convenes Friday

How do I ask for a date? Should I speak to strangers when riding in an elevator? At what point in an interview should I ask about salary range? How do I write a pleasant thank-you note for a gift I hated? Should I use my cell phone while walking down Newbury Street? Do I tip the mailperson?

The answers to these questions and many others may be found during the 10th session of MIT's Charm School Friday, Jan. 31 from noon to 5 p.m. at the Student Center.

Ambitious students may earn "charm credits" toward a formal Charm School degree. A Bachelor's degree is awarded for completing six subjects, a Master's for eight, and a Ph.D. for 12. Degrees will be awarded at commencement ceremonies at the end of the day.

Charm School will feature a fashion show from 4-5 p.m. in the Lobdell Dining Area (W20), with student models wearing the most recent fashions in business casual, business suits and special office occasion attire from sponsors Tellos, Keezer's and Jacobs.

For more information, refer to the Charm School web site or contact Tom Robinson at 253-7605 or trob@mit.edu.

Six pamphleteers make tiny books

Just follow the signs: a right turn, through the library doors, down the stairs, a sharp left, two more lefts, a right, and finally through a doorway. That's how we found our way through the basement bookshelves to the Libraries' Preservation Services workshop, where six students learned how to make small paper books using artfully designed papers, scissors, awl, needle and thread.

Their little books were different sizes, with delightfully colored and patterned paper covers and hand-sewn bindings. One student used linen thread enhanced with beeswax, another used a bright green embroidery-like thread to bind her six-page book.

Nils Nordal, assistant director of the Center for Innovation in Product Development, read from an instruction sheet as he tried for the second time to bind his third book. "Go around this one and up through here," he said as he pulled thread through the centerfold of a small sheaf of folded cream-colored paper. "What I didn't do the first time was bring these ends to either side of this string, so it was going to be too loose," he explained, preparing to tie off his binding threads.

Nordal said he took the class to do "something fun." During IAP, "you get the chance to go do something that has nothing to do with your background, with your work, with your course of study," he said. He plans to teach pamphlet-making to his young niece.

Heather Kaufman, a preservation services librarian, taught the class with two of her co-workers. "With bookmaking, you never stop learning," she said. "Whatever materials you're using, you learn about them. For instance, if you're using leather, you learn about tanning."

Denise Brehm

Seeing the child's inner ear

Do you ever wonder what the doctor sees when she shines a light into your or your child's ear? A normal eardrum is light pink and so transparent that she can see the middle ear's three bones behind it. An inflamed, infected ear, however, has a red eardrum that is not transparent, and may even bulge with built-up fluid. Negative pressure in the inner ear can even cause the eardrum to be sucked inward and burst.

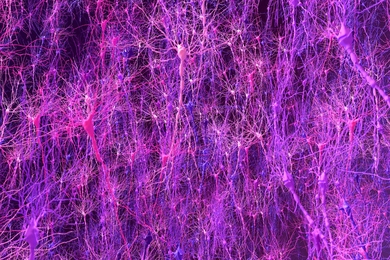

Holden Cheng, a graduate student in the Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology, gave a talk as part of the Speech and Hearing Bioscience and Technology Lecture Series Jan. 24 about the various ailments that can affect our speech and hearing and how those ailments manifest themselves in clinical settings. These ailments range from easily curable ear infections to incessant tinnitus, or ringing in the ears, that affects 50 million Americans, 12 million of them severely. This phantom annoyance, in which patients hear a constant ringing or hissing noise that doesn't exist in the environment, has driven some victims to suicide.

Tinnitus is idiopathic, which means doctors can't put their finger on the cause and there is no cure, but advances in brain imaging show that tinnitus is an ailment of the central nervous system and not the ear. Before this knowledge, doctors would sometimes sever the auditory nerve in the hope of giving their patients some relief from the incessant sound, only to find that this didn't stop the ringing. In fact, it was worse because it was the only sound their deafened patients could hear.

Deborah Halber

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on January 29, 2003.