Far-reaching effects of structural racism can be seen in all facets of American life. This year, as Americans witnessed widespread demonstrations stemming from racial injustice at the hands of officers in law enforcement, a ground swell of conversations about race and pleas for action emerged.

One area in which racism has had significant effects is health care equity, a fact that has been exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic. In light of current events, members of the MIT community involved in the successful hackathons MIT Covid-19 Challenge and MIT Hacking Medicine sought to explore the role of racism embedded in U.S. health care structures. More specifically, how could they tear down racism in health care using proven hackathon methodology traditionally applied to other complex health care problems?

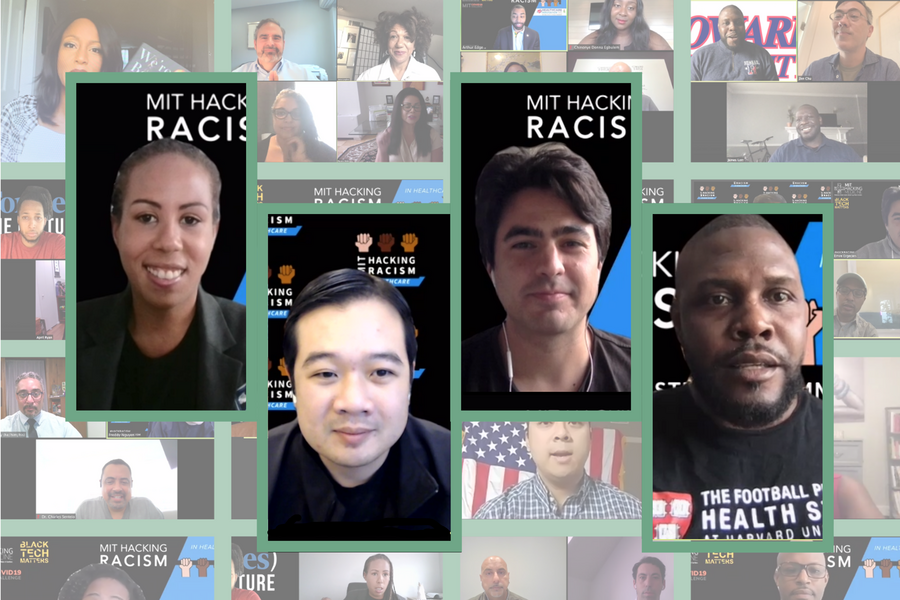

With these questions in mind, a team of MIT students, postdocs, and others, in collaboration with the nonprofit organization Black Tech Matters, began engaging the community both within and outside the walls of MIT to galvanize individuals, stakeholders, and communities from different personal and professional backgrounds to unite by a call to action. As health hackathons have been used by an increasingly wide range of organizations to solve tough and diverse health care problems and harness future business opportunities, the group organized a unique virtual hackathon, MIT Hacking Racism in Healthcare. Designed in a 48-hour sprint format, the event takes place Oct. 16-18, and is open to all interested participants. Three of the organizers, Freddy Nguyen, a research fellow with the MIT Innovation Initiative; Emre Ergecen, a graduate student in electrical engineering and computer science; and Charles Senteio, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Visiting Assistant Professor in the MIT Sloan School of Management, spoke recently on how collective action can be spurred by crowdsourced events such as hackathons.

Q: What barriers keep people from being adequately represented and served in health care?

A: Health disparities, sometimes referred to as health inequities, have garnered an increasing amount of attention from physicians and health policy experts, as well as a renewed focus from federal health agencies. Differential access to medical care and treatment modalities, and disparate outcomes among various racial and ethnic groups have been reported in numerous studies. “Drivers” of such differences include disparate costs and varying access to the health care system, primary care physicians, and preventive health services. The complexities of this issue speak to its contributing factors, which range from distrust between people of color and the medical and research communities; to differing levels of access to health care services, educational opportunities, jobs, and leadership opportunities based on socioeconomic factors; to biases inherent to the current health care system in how medicine is taught and practiced; to social determinants of health that contribute to the widening disparities observed.

Q: Why are hackathons a strong format for addressing the issue of racial injustice?

A: In this sense, a “hack” is a creative use of ingenuity to develop a solution to an existing problem using intense interdisciplinary teamwork in a marathon timeframe. Thus, a “hackathon” is an intensive sprint to solve complex challenges using an environment conducive to iterating and surfacing the best ideas possible from a particular group. Hackathons are commonly associated with programming and computer science but in health hackathons, pioneered by MIT Hacking Medicine, not all participants are coders. In fact, they come from diverse backgrounds — from patients to business managers to scientists to clinicians to engineers to user designers to payers — all to co-define the pain points, and to co-develop the most innovative solutions with the best viability and feasibility. Such events can bring together participants spanning the whole health care ecosystem. Together they attack health care challenges using a multi-stakeholder and problem-centric approach focused on the real end-user needs. Hackathons also facilitate the presence of hundreds of mentors that come online to help teams iterate throughout the weekend, providing their subject matter and process driven expertise providing accelerated customer discovery, market landscape research, and external objective feedback to hackathon teams.

Q: In light of social unrest, many equality and diversity initiatives have sprouted up at institutions around the country. What makes the MIT Hacking Racism in Healthcare stand out?

A: From our perspective, a hackathon is an efficient tool to raise awareness about complex issues, empower individuals to find solutions, and to focus on actionable change. The MIT Hacking Racism in Healthcare Challenge is not only a problem-solving hackathon but a venue for the MIT community to stop and think about the biases and racial disparities ingrained in the healthcare system. Organizing a hackathon about racial disparities in health care entails much more than its logistics. It is crucial for a hackathon to involve and meaningfully engage with grassroots efforts, appropriate stakeholders, and the people negatively affected by discrimination and racist policies in health care. We partnered with Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU), health care providers, and social impact organizations that helped us identify, define, and prioritize the problems in this space, and more importantly become more educated ourselves. We even hosted a listening summit last month, prior to the main hackathon event, in order to educate ourselves, the participants, and the community, which gave everyone a chance to interact with leading experts in the field.

Of course, it is impossible to address the complex nature of racial disparities in health care during a two-day hackathon event, but what is possible is overcoming the initial barrier of recognizing the issues, defining the problems, bringing the community together, and removing the barriers to collaborations. Making an impact and building anti-racist platforms in the health care space requires a concerted effort with sustained support from mentors, health care providers, patients, and every stakeholder of the health care ecosystem. We will also provide post-hackathon support — everything from mentorship to help with arranging incubator/accelerator opportunities — to every team that chooses to continue after the hackathon weekend and that is willing to actualize their ideas.