Imagine moving from state to state while growing up in the U.S., transferring between high schools, and eventually attending college out of state. The first two events might seem disruptive, and the third involves departing a local community. And yet, these things may be exactly what helps some people thrive later in life.

That’s one implication of a newly published study about social networks co-authored by an MIT professor, which finds that so-called long ties — connections between people who otherwise lack any mutual contacts — are highly associated with greater economic success in life. Those long ties are fostered partly by turning points such as moving between states, and switching schools.

The study, based on a large quantity of Facebook data, both illuminates how productive social networks are structured and identifies specific life events that significantly shape people’s networks.

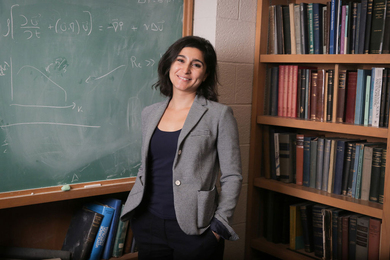

“People who have more long ties [on Facebook], and who have stronger long ties, have better economic indicators,” says Dean Eckles, an MIT professor and co-author of a new paper detailing the study’s findings.

“Our hope is that the study provides better evidence of this really strong relationship, at the scale of the entire U.S,” Eckles says. “There hasn’t really been this sort of investigation into those types of disruptive life events.”

The paper, “Long ties, disruptive life events, and economic prosperity,” appears in open-access form in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The authors are Eaman Jahani PhD ’21, a postdoc and lecturer at the University of California at Berkeley, who received his doctorate from MIT’s Institute for Data, Systems, and Society, and the Statistics and Data Science Center; Samuel P. Fraiberger, a data scientist at the World Bank; Michael Bailey, an economist and research scientist manager at Meta Platforms (which operates Facebook); and Eckles, an associate professor of marketing at MIT Sloan School of Management. Jahani, who worked at Meta when the study was conducted, performed the initial research, and the aggregate data analysis protected the privacy of individuals in compliance with regulations.

On the move

In recent decades, scholars have often analyzed social networks while building on a 1973 study by Stanford University’s Mark Granovetter, “The Strength of Weak Ties,” one of the 10 most-cited social science papers of all time. In it, Granovetter postulated that a network’s “weak ties”— the people you know less well — are vital. Your best friends may have networks quite similar to your own, but your “weak ties” provide additional connections useful for employment, and more. Granovetter also edited this current paper for PNAS.

To conduct the study, the scholars mapped all reciprocal interactions among U.S.-based Facebook accounts from December 2020 to June 2021, to build a data-rich picture of social networks in action. The researchers maintain a distinction between “long” and “short” ties; in this definition, long ties have no other mutual connections at all, while short ties have some.

Ultimately the scholars found that, when assessing everyone who has lived in the same state since 2012, those who had previously moved among U.S. states had 13 percent more long ties on Facebook than those who had not. Similarly, people who had switched high schools had 10 percent more long ties than people who had not.

Facebook does not have income data for its users, so the scholars used a series of proxy measures to evaluate financial success. People with more long ties tend to live in higher-income areas, have more internet-connected devices, use more expensive mobile phones, and make more donations to charitable causes, compared to those who do not.

Additionally, the research evaluates whether or not moving among states, or switching schools, is itself what causes people to have more long ties. After all, it could be the case that families who move more often have qualities that lead family members to be more proactive about forging ties with people.

To examine this, the research team analyzed a subgroup of Facebook users who had switched high schools only when their first high school closed — meaning it was not their choice to change. Those people had 6 percent more long ties than those who had attended the same high schools but not been forced to switch; given this common pool of school attendees forced into divergent circumstances, the evidence suggests that making the school change itself “shapes the proclivity to connect with different communities,” as the scholars write in the paper.

“It’s a plausibly random nudge,” Eckles says, “and we find the people who were exposed to these high school closures end up with more long ties. I think that is one of the compelling elements pointing toward a causal story here.”

Three types of events, same trend

As the scholars acknowledge in the paper, there are some limitations to the study. Because it focuses on Facebook interactions, the research does not account for offline activities that may sustain social networks. It is also likely that economic success itself shapes people’s social networks, and not just that networks help shape success. Some people may have opportunities to maintain long ties, through professional work or travel, that others do not.

On the other hand, the study does uncover long-term social network ties that had not been evaluated before, and, as the authors write,”having three different types of events — involving different processes by which people are selected into the disruption — pointing to the same conclusions makes for a more robust and notable pattern.”

Other scholars in the field believe the study is a notable piece of research. In a commentary on the paper also published in PNAS, Michael Macy, a sociology professor at Cornell University, writes that “the authors demonstrate the importance of contributing to cumulative knowledge by confirming hypotheses derived from foundational theory while at the same time elaborating on what was previously known by digging deeper into the underlying causal mechanisms. In short, the paper is must reading not only for area specialists but for social scientists across the disciplines.”

For his part, Eckles emphasizes that the researchers are releasing anonymized data from the study, so that other scholars can build on it, and develop additional insights about social network structure, while complying with all privacy regulations.

“We’ve released [that] data and made it public, and we’re really happy to be doing that,” Eckles says. “We want to make as much of this as possible open to others. That’s one of the things that I’m hoping is part of the broader impact of the paper.”

Jahani worked as a contractor at Meta Platforms, which operates Facebook, while conducting the research. Eckles has received past funding from Meta, as well as conference sponsorship, and previously worked there, before joining MIT.