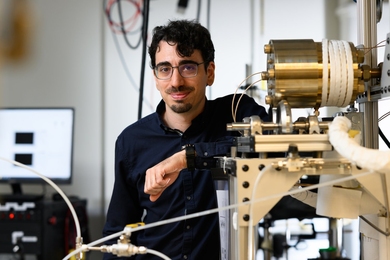

By his own admission, Héctor Javier Vázquez Martínez was underprepared to move to Zurich for a semester during his junior year. His cell phone plan didn’t work, he’d forgotten to change his money, and he didn’t know German. However, it didn’t take him long to find his way. Soon, the electrical engineering and computer science major was working in a lab at the University of Zurich and ETH Zurich’s Institute of Neuroinformatics, developing a computer model of how mice learn.

In his native Puerto Rico, Vázquez Martínez says, Switzerland was viewed as a sort of near-perfect country, which he only dreamed of visiting. Two previous summer internships had also left him feeling uncertain about what he wanted to do with his future. When he received an email about a departmental exchange between MIT and ETH Zurich, he knew it was an opportunity he couldn’t pass up.

Through the kindness of strangers who soon became friends, it all worked out for Vázquez Martínez. A member of the rowing club he joined helped him to learn German as he helped her refine her Spanish. When he began his research position, he would commute to work with a labmate. The research project turned out to be a great fit for Vázquez Martínez, whose initial interest in machine learning had led to a passionate curiosity about how humans think.

“The time that followed more than made up for the first rough couple of weeks. I would do it all over again if I had the chance,” he says.

Spending a semester in Switzerland is just one of many opportunities at MIT that the adventurous senior has seized. During his four years as an MIT student, he has taught underprivileged students abroad, joined the crew team and the Cuban salsa group Casino Rueda, and even dipped into the world of music theory.

Defying expectations

During his first year, Vázquez Martínez spent three weeks in Chile as part of the MISTI Global Teaching Labs program. The plan had been to teach physics to kids from two middle- and low-income high schools during their summer break. But students from those schools generally enter the work force right after graduation. When he got there, Vázquez Martínez realized something more practical would be a better fit.

“My one and only reaction was, well … what good am I going to do you if I’m just teaching you physics?” he recalls. “This is just not going to help you when you graduate.”

A professor told Vázquez Martínez that the students could already wire and solder little electronic devices called Arduinos, but they didn’t know how to program them. Over the next few weeks, Vázquez Martínez improvised a curriculum for the high schoolers, teaching them how to program the devices on their own.

Then, in the summer following his first year, he participated in a program called Facebook University sponsored by the social media giant. He was given five weeks to develop an IOS app, which he said was generally expected to be a social networking app.

“I thought, well, the market is full of those. I want to do something that actually helps people,” he says.

Instead, Vázquez Martínez worked on an app that could translate the American Sign Language alphabet into text. While his team was only able to get the app working for four or so letters in that time period, they were able to present a fully functional proof of concept.

Thinking on the brain

His work with Facebook University sparked an interest in Vázquez Martínez for the field of machine learning. So, in his sophomore year, he took a class on artificial intelligence. To his surprise, he found that machine learning itself didn’t fascinate him.

“It’s mostly fancy statistics,” he says. “As I was taking the course, I found that I was a lot more interested in figuring out, why does this work? Why do we think this way? And why can I recognize a dog by just seeing a dog, as opposed to giving a computer 10,000 pictures of a dog and then maybe it’ll say it’s a dog and not a cat?”

Vázquez Martínez also became involved that year with neural network research by Glen Urban, the David Austin Professor in Marketing, Emeritus, in the Sloan School of Management. Basically, a computer would be fed thousands of descriptions of customers and lists of credit cards they applied for, and the program would predict which credit cards people with certain demographics would apply for. Vázquez Martínez took over the work from a student who graduated, and enjoyed having his own project. But come fall of his junior year, he decided it was time for a change of scenery, and he was off to Switzerland.

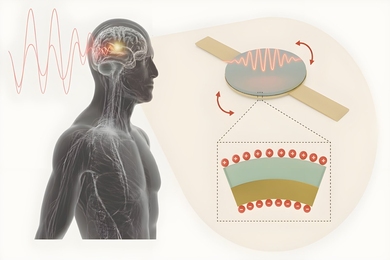

His research at the Institute of Neuroinformatics in Switzerland was related to a previous experiment, in which mice were taught to recognize different sandpaper surfaces using a system of positive and negative rewards. The way mice identify their surroundings is through neurons in their whiskers that relay information to their brains. Vázquez Martínez was assigned to make a computational model of three clusters of neurons in a mouse’s brain, and to teach the model to distinguish between different types of sandpaper the way mice do.

An active life

Vázquez Martínez has taken up music as a hobby, and recently completed 21M.051 (Fundamentals of Music). In the class, he learned introductory music theory through playing the piano. While he says he’s still at a pretty basic level of knowledge, it helps him to communicate with his younger brother who has been studying music from a very early age. They exchange pieces of theory that they’ve learned, show off songs they’ve picked up, and have even tried to compose a piano piece together.

Vázquez Martínez is also a member of the dance group Casino Rueda and averages about six to seven hours of dancing a week.

He started with the group as a beginner four years ago, and now leads some of the advanced sessions. Through dedicated practice, he says, “I found a love for the dance, the music, and how it allows me to communicate with other people. I am continually challenged by our practices and the other dancers, and feel a new rush of adrenaline with every choreography and performance.”

Vázquez Martínez also rows for lightweight men’s crew team. “I walked onto the crew team my first year having never seen a rowing oar in my life,” he says. “For me, it was an enormous step up in terms of dedication to a sport, but I stuck to it because I felt constantly forced to push the limits of what I thought I could physically and mentally do. In the words of my current team captain: ‘It is the purest form of teamwork.’”

As for Vázquez Martínez’s future, he’s still deciding on the specifics. After his time in Chile, he’s interested in teaching at home at Puerto Rico. And of course, he’s still captivated by his search to understand how people think. He’s not sure exactly what his next project will look like — but he says he’ll know it’s a good match when he wakes up thinking about his work.