An MIT student team took second place for its design of a multilevel greenhouse to be used on Mars in NASA’s 2019 Breakthrough, Innovative and Game-changing (BIG) Idea Challenge last month.

Each year, NASA holds the BIG Idea competition in its search for innovative and futuristic ideas. This year’s challenge invited universities across the United States to submit designs for a sustainable, cost-effective, and efficient method of supplying food to astronauts during future crewed explorations of Mars. Dartmouth College was awarded first place in this year’s closely contested challenge.

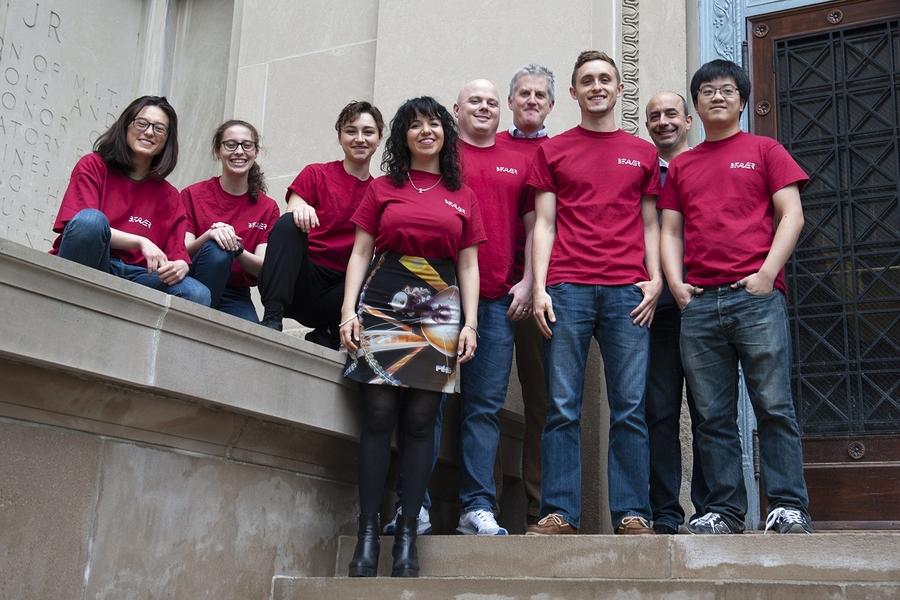

“This was definitely a full-team success,” says team leader Eric Hinterman, a graduate student in MIT’s Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AeroAstro). The team had contributions from 10 undergraduates and graduate students from across MIT departments. Support and assistance were provided by four architects and designers in Italy. This project was completely voluntary; all 14 contributors share a similar passion for space exploration and enjoyed working on the challenge in their spare time.

The MIT team dubbed its design “BEAVER” (Biosphere Engineered Architecture for Viable Extraterrestrial Residence). “We designed our greenhouse to provide 100 percent of the food requirements for four active astronauts every day for two years,” explains Hinterman.

The ecologists and agriculture specialists on the MIT team identified eight types of crops to provide the calories, protein, carbohydrates, and oils and fats that astronauts would need; these included potatoes, rice, wheat, oats, and peanuts. The flexible menu suggested substitutes, depending on astronauts’ specific dietary requirements.

“Most space systems are metallic and very robotic,” Hinterman says. “It was fun working on something involving plants.”

Parameters provided by NASA — a power budget, dimensions necessary for transporting by rocket, the capacity to provide adequate sustenance — drove the shape and the overall design of the greenhouse.

Last October, the team held an initial brainstorming session and pitched project ideas. The iterative process continued until they reached their final design: a cylindrical growing space 11.2 meters in diameter and 13.4 meters tall after deployment.

An innovative design

The greenhouse would be packaged inside a rocket bound for Mars and, after landing, a waiting robot would move it to its site. Programmed with folding mechanisms, it would then expand horizontally and vertically and begin forming an ice shield around its exterior to protect plants and humans from the intense radiation on the Martian surface.

Two years later, when Earth and Mars orbits were again in optimal alignment for launching and landing, a crew would arrive on Mars, where they would complete the greenhouse setup and begin growing crops. “About every two years, the crew would leave and a new crew of four would arrive and continue to use the greenhouse,” explains Hinterman.

To maximize space, BEAVER employs a large spiral that moves around a central core within the cylinder. Seedlings are planted at the top and flow down the spiral as they grow. By the time they reach the bottom, the plants are ready for harvesting, and the crew enters at the ground floor to reap the potatoes and peanuts and grains. The planting trays are then moved to the top of the spiral, and the process begins again.

“A lot of engineering went into the spiral,” says Hinterman. “Most of it is done without any moving parts or mechanical systems, which makes it ideal for space applications. You don’t want a lot of moving parts or things that can break.”

The human factor

“One of the big issues with sending humans into space is that they will be confined to seeing the same people every day for a couple of years,” Hinterman explains. “They’ll be living in an enclosed environment with very little personal space.”

The greenhouse provides a pleasant area to ensure astronauts’ psychological well-being. On the top floor, just above the spiral, a windowed “mental relaxation area” overlooks the greenery. The ice shield admits natural light, and the crew can lounge on couches and enjoy the view of the Mars landscape. And rather than running pipes from the water tank at the top level down to the crops, Hinterman and his team designed a cascading waterfall at the area’s periphery, further adding to the ambiance.

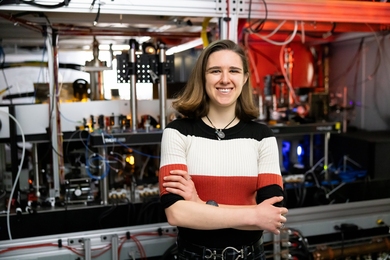

Sophomore Sheila Baber, an Earth, atmospheric, and planetary sciences (EAPS) major and the team’s ecology lead, was eager to take part in the project. “My grandmother used to farm in the mountains in Korea, and I remember going there and picking the crops,” she says. “Coming to MIT, I felt like I was distanced from my roots. I am interested in life sciences and physics and all things space, and this gave me the opportunity to combine all those.”

Her work on BEAVER led to Baber’s award of one of five NASA internships at Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia this summer. She expects to continue exploration of the greenhouse project and its applications on Earth, such as in urban settings where space for growing food is constrained.

“Some of the agricultural decisions that we made about hydroponics and aquaponics could potentially be used in environments on Earth to raise food,” she says.

“The MIT team was great to work with,” says Hinterman. “They were very enthusiastic and hardworking, and we came up with a great design as a result.”

In addition to Baber and Hinterman, team members included Siranush Babakhanova (Physics), Joe Kusters (AeroAstro), Hans Nowak (Leaders for Global Operations), Tajana Schneiderman (EAPS), Sam Seaman (Architecture), Tommy Smith (System Design and Management), Natasha Stamler (Mechanical Engineering and Urban Studies and Planning), and Zhuchang Zhan (EAPS). Assistance was provided by Italian designers and architects Jana Lukic, Fabio Maffia, Aldo Moccia, and Samuele Sciarretta. The team’s advisors were Jeff Hoffman, Sara Seager, Matt Silver, Vladimir Aerapetian, Valentina Sumini, and George Lordos.

The BIG Idea Challenge is sponsored by NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate’s Game Changing Development program and managed by the National Institute of Aerospace.