Using a technique that can precisely edit DNA bases, MIT researchers have created a way to store complex “memories” in the DNA of living cells, including human cells.

The new system, known as DOMINO, can be used to record the intensity, duration, sequence, and timing of many events in the life of a cell, such as exposures to certain chemicals. This memory-storage capacity can act as the foundation of complex circuits in which one event, or series of events, triggers another event, such as the production of a fluorescent protein.

“This platform gives us a way to encode memory and logic operations in cells in a scalable fashion,” says Fahim Farzadfard, a Schmidt Science Postdoctoral Fellow at MIT and the lead author of the paper. “Similar to silicon-based computers, in order to create complex forms of logic and computation, we need to have access to vast amounts of memory.”

Applications for these types of complex memory circuits include tracking the changes that occur from generation to generation as cells differentiate, or creating sensors that could detect, and possibly treat, diseased cells.

Timothy Lu, an MIT associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science and of biological engineering, is the senior author of the study, which appears in the Aug. 22 issue of Molecular Cell. Other authors of the paper include Harvard University graduate student Nava Gharaei, former MIT researcher Yasutomi Higashikuni, MIT graduate student Giyoung Jung, and MIT postdoc Jicong Cao.

Written in DNA

Several years ago, Lu’s lab developed a memory storage system based on enzymes called DNA recombinases, which can “flip” segments of DNA when a specific event occurs. However, this approach is limited in scale: It can only record one or two events, because the DNA sequences that have to be flipped are very large, and each requires a different recombinase.

Lu and Farzadfard then developed a more targeted approach in which they could insert new DNA sequences into predetermined locations in the genome, but that approach only worked in bacterial cells. In 2016, they developed a memory storage system based on CRISPR, a genome-editing system that consists of a DNA-cutting enzyme called Cas9 and a short RNA strand that guides the enzyme to a specific area of the genome.

This CRISPR-based process allowed the researchers to insert mutations at specific DNA locations, but it relied on the cell’s own DNA-repair machinery to generate mutations after Cas9 cut the DNA. This meant that the mutational outcomes were not always predictable, thus limiting the amount of information that could be stored.

The new DOMINO system uses a variant of the CRISPR-Cas9 enzyme that makes more well-defined mutations because it directly modifies and stores bits of information in DNA bases instead of cutting DNA and waiting for cells to repair the damage. The researchers showed that they could get this system to work accurately in both human and bacterial cells.

“This paper tries to overcome all the limitations of the previous ones,” Lu says. “It gets us much closer to the ultimate vision, which is to have robust, highly scalable, and defined memory systems, similar to how a hard drive would work.”

To achieve this higher level of precision, the researchers attached a version of Cas9 to a recently developed “base editor” enzyme, which can convert the nucleotide cytosine to thymine without breaking the double-stranded DNA.

Guide RNA strands, which direct the base editor where to make this switch, are produced only when certain inputs are present in the cell. When one of the target inputs is present, the guide RNA leads the base editor either to a stretch of DNA that the researchers added to the cell’s nucleus, or to genes found in the cell’s own genome, depending on the application. Measuring the resulting cytosine to thymine mutations allows the researchers to determine what the cell has been exposed to.

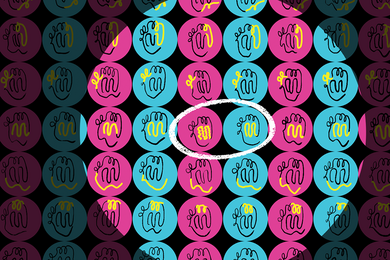

“You can design the system so that each combination of the inputs gives you a unique mutational signature, and from that signature you can tell which combination of the inputs has been present,” Farzadfard says.

Complex calculations

The researchers used DOMINO to create circuits that perform logic calculations, including AND and OR gates, which can detect the presence of multiple inputs. They also created circuits that can record cascades of events that occur in a certain order, similar to an array of dominos falling.

“This is very innovative work that enables recording and retrieving cellular information using DNA. The ability to perform sequential or logic computation and associative learning is particularly impressive,” says Wilson Wong, an associate professor of biomedical engineering at Boston University, who was not involved in the research. “This work highlights novel genetic circuits that can be achieved with CRISPR/Cas.”

Most previous versions of cellular memory storage have required stored memories to be read by sequencing the DNA. However, that process destroys the cells, so no further experiments can be done on them. In this study, the researchers designed their circuits so that the final output would activate the gene for green fluorescent protein (GFP). By measuring the level of fluorescence, the researchers could estimate how many mutations had accumulated, without killing the cells. The technology could potentially be used to create mouse immune cells that produce GFP when certain signaling molecules are activated, which researchers could analyze by periodically taking blood samples from the mice.

Another possible application is designing circuits that can detect gene activity linked to cancer, the researchers say. Such circuits could also be programmed to turn on genes that produce cancer-fighting molecules, allowing the system to both detect and treat the disease. “Those are applications that may be further away from real-world use but are certainly enabled by this type of technology,” Lu says.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Office of Naval Research, the National Science Foundation, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, the MIT Center for Microbiome Informatics and Therapeutics, and the NSF Expeditions in Computing Program Award.