The work of a science writer, including this one, includes reading journal papers filled with specialized technical terminology, and figuring out how to explain their contents in language that readers without a scientific background can understand.

Now, a team of scientists at MIT and elsewhere has developed a neural network, a form of artificial intelligence (AI), that can do much the same thing, at least to a limited extent: It can read scientific papers and render a plain-English summary in a sentence or two.

Even in this limited form, such a neural network could be useful for helping editors, writers, and scientists scan a large number of papers to get a preliminary sense of what they’re about. But the approach the team developed could also find applications in a variety of other areas besides language processing, including machine translation and speech recognition.

The work is described in the journal Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, in a paper by Rumen Dangovski and Li Jing, both MIT graduate students; Marin Soljačić, a professor of physics at MIT; Preslav Nakov, a principal scientist at the Qatar Computing Research Institute, HBKU; and Mićo Tatalović, a former Knight Science Journalism fellow at MIT and a former editor at New Scientist magazine.

From AI for physics to natural language

The work came about as a result of an unrelated project, which involved developing new artificial intelligence approaches based on neural networks, aimed at tackling certain thorny problems in physics. However, the researchers soon realized that the same approach could be used to address other difficult computational problems, including natural language processing, in ways that might outperform existing neural network systems.

“We have been doing various kinds of work in AI for a few years now,” Soljačić says. “We use AI to help with our research, basically to do physics better. And as we got to be more familiar with AI, we would notice that every once in a while there is an opportunity to add to the field of AI because of something that we know from physics — a certain mathematical construct or a certain law in physics. We noticed that hey, if we use that, it could actually help with this or that particular AI algorithm.”

This approach could be useful in a variety of specific kinds of tasks, he says, but not all. “We can’t say this is useful for all of AI, but there are instances where we can use an insight from physics to improve on a given AI algorithm.”

Neural networks in general are an attempt to mimic the way humans learn certain new things: The computer examines many different examples and “learns” what the key underlying patterns are. Such systems are widely used for pattern recognition, such as learning to identify objects depicted in photos.

But neural networks in general have difficulty correlating information from a long string of data, such as is required in interpreting a research paper. Various tricks have been used to improve this capability, including techniques known as long short-term memory (LSTM) and gated recurrent units (GRU), but these still fall well short of what’s needed for real natural-language processing, the researchers say.

The team came up with an alternative system, which instead of being based on the multiplication of matrices, as most conventional neural networks are, is based on vectors rotating in a multidimensional space. The key concept is something they call a rotational unit of memory (RUM).

Essentially, the system represents each word in the text by a vector in multidimensional space — a line of a certain length pointing in a particular direction. Each subsequent word swings this vector in some direction, represented in a theoretical space that can ultimately have thousands of dimensions. At the end of the process, the final vector or set of vectors is translated back into its corresponding string of words.

“RUM helps neural networks to do two things very well,” Nakov says. “It helps them to remember better, and it enables them to recall information more accurately.”

After developing the RUM system to help with certain tough physics problems such as the behavior of light in complex engineered materials, “we realized one of the places where we thought this approach could be useful would be natural language processing,” says Soljačić, recalling a conversation with Tatalović, who noted that such a tool would be useful for his work as an editor trying to decide which papers to write about. Tatalović was at the time exploring AI in science journalism as his Knight fellowship project.

“And so we tried a few natural language processing tasks on it,” Soljačić says. “One that we tried was summarizing articles, and that seems to be working quite well.”

The proof is in the reading

As an example, they fed the same research paper through a conventional LSTM-based neural network and through their RUM-based system. The resulting summaries were dramatically different.

The LSTM system yielded this highly repetitive and fairly technical summary: “Baylisascariasis,” kills mice, has endangered the allegheny woodrat and has caused disease like blindness or severe consequences. This infection, termed “baylisascariasis,” kills mice, has endangered the allegheny woodrat and has caused disease like blindness or severe consequences. This infection, termed “baylisascariasis,” kills mice, has endangered the allegheny woodrat.

Based on the same paper, the RUM system produced a much more readable summary, and one that did not include the needless repetition of phrases: Urban raccoons may infect people more than previously assumed. 7 percent of surveyed individuals tested positive for raccoon roundworm antibodies. Over 90 percent of raccoons in Santa Barbara play host to this parasite.

Already, the RUM-based system has been expanded so it can “read” through entire research papers, not just the abstracts, to produce a summary of their contents. The researchers have even tried using the system on their own research paper describing these findings — the paper that this news story is attempting to summarize.

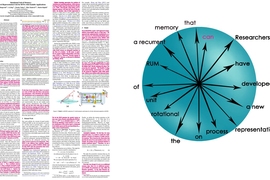

Here is the new neural network’s summary: Researchers have developed a new representation process on the rotational unit of RUM, a recurrent memory that can be used to solve a broad spectrum of the neural revolution in natural language processing.

It may not be elegant prose, but it does at least hit the key points of information.

Çağlar Gülçehre, a research scientist at the British AI company Deepmind Technologies, who was not involved in this work, says this research tackles an important problem in neural networks, having to do with relating pieces of information that are widely separated in time or space. “This problem has been a very fundamental issue in AI due to the necessity to do reasoning over long time-delays in sequence-prediction tasks,” he says. “Although I do not think this paper completely solves this problem, it shows promising results on the long-term dependency tasks such as question-answering, text summarization, and associative recall.”

Gülçehre adds, “Since the experiments conducted and model proposed in this paper are released as open-source on Github, as a result many researchers will be interested in trying it on their own tasks. … To be more specific, potentially the approach proposed in this paper can have very high impact on the fields of natural language processing and reinforcement learning, where the long-term dependencies are very crucial.”

The research received support from the Army Research Office, the National Science Foundation, the MIT-SenseTime Alliance on Artificial Intelligence, and the Semiconductor Research Corporation. The team also had help from the Science Daily website, whose articles were used in training some of the AI models in this research.