It’s the holiday season, which to many people means a season of giving — to loved ones, colleagues, public radio and television, or to any number of the countless charities seeking support. Nearly a third of all annual charitable giving occurs in December, and many nonprofits raise as much as half of their annual funds from this year-end burst of giving.

With so many charities relying on these donations to achieve their goals, how do we choose between them? How do we know how much impact our dollars actually have?

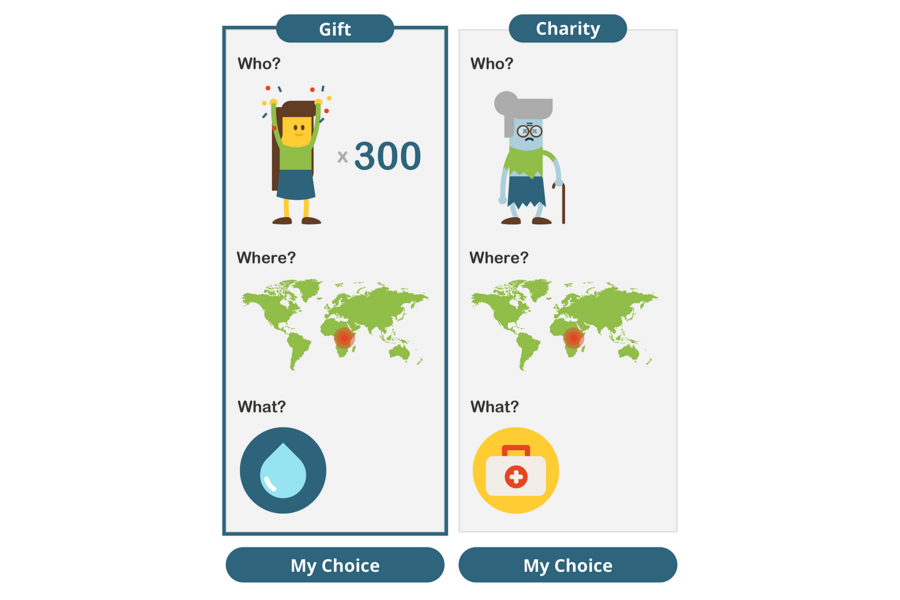

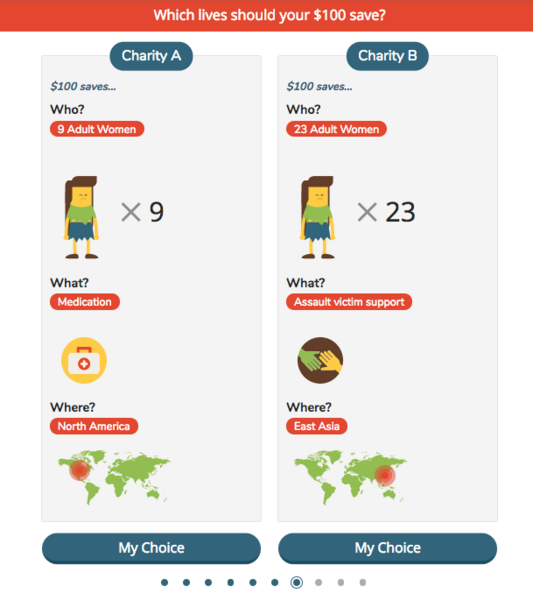

Enter MyGoodness: an online game that aims to maximize the impact of charitable donations. Created by Iyad Rahwan and Edmond Awad of the MIT Media Lab’s Scalable Cooperation group, MyGoodness presents each player with a hypothetical $1,000 to spend on donations to various causes. Players are then faced with a series of 10 sets of choices between different charities, giving away $100 at each turn. By choosing between numbers and characteristics of people, geographic location, and types of aid, players are invited to better understand the effectiveness of their donation choices.

The MyGoodness team collaborated on the game with The Life You Can Save (TLYCS), a nonprofit organization founded by Peter Singer that identifies charities that deliver maximum impact. TLYCS helped with the design and advised the researchers on the magnitude of the different tradeoffs between charities. TLYCS is also helping MyGoodness back up its goals with real money: Two players will be randomly selected to receive $1,000 in real money to put toward their actual decisions in the game.

“We’re trying to promote a specific idea, which is that goodness is doing the best thing for the greatest number of people,” says Rawan, head of the Scalable Cooperation group. “This game is about life-saving charities, through different means: clean water, nutritious meals, medication, assault victim support. We take the position that saving the greatest number of lives is the right thing to do, regardless of where they are or how you’re saving them. Every life is the same and saving more lives is the ideal.”

MyGoodness takes players to some uncomfortable places, sharply underscoring certain biases and preferences. Like a charity-based trolley problem, the game asks us to choose, for example, between providing nutritious meals to 10 children in North America, or clean water to 25 people in northern Africa.

“Currently, only 6 percent of U.S. charitable donations go toward international causes, where you can get the most bang for your buck,” explains Charlie Besler, executive director of The Life You Can Save. “Meanwhile, every day, over 7,500 children die from preventable causes. We're trying to get people to reconsider the notion that all donations should go to domestic causes, and to give in a thoughtful way.”

It’s easy to let our own experiences and biases dictate our decisions. It’s also easy to choose a charity that looks good, based on little or no information (only about 35 percent of people do any research before giving to a charity). MyGoodness seeks to promote a more objective, efficacy-based process, even if it means overcoming an impulse to favor one type of person over another.

“We want people to reflect on the values they use when they decide how to give to charity. The game presents different merits to them, they confront the discomfort that comes with choosing, and in the process learn something about themselves,” says Rahwan.

By offering the real cash incentive in selecting two random players to receive $1,000 (one on Christmas, the other on New Year’s day), the team hopes MyGoodness will make people feel that they have a real stake in the game. This is doubly true since the game does offer the option to keep some money or give it to a relative, which means that if either of the two players who wins the real money has made those choices in the game, that’s what will happen.

But the MyGoodness team is confident that players will embrace the opportunity to reflect on effective giving, as well as choose more effectively.

“We know that people are good. We want to help them be better,” Rahwan says.

MyGoodness can be played at mygoodness.mit.edu.