Imagine you are receiving a refund payment from the federal government. Are you going to spend it right away or save the money? Is that decision based on your short-term finances? Or does it hinge on whether you identify yourself as a “spender” or a “saver” more generally?

A new study by an MIT economist sheds more light on the quirks of people’s actions in such cases and suggests that, in addition to immediate financial needs, persistent behavioral characteristics play a key role in even short-term pocketbook decisions.

The study examines the 2008 economic stimulus payments the U.S. federal government sent to households across the nation. The study’s rather nuanced findings indicate that while people do “smooth” their consumption by spending or saving money based on their own liquidity — as canonical economic theory holds — some longer-term factors are at play as well.

For starters, other things being equal, lower historical incomes, not just short-term fluctuations in income, match a greater tendency to spend money right away. Beyond that, people who describe themselves as habitual “spenders” will plow through newfound money more quickly. This adds credence to the idea that larger behavioral tendencies, not just rational calculations, help drive financial decisions.

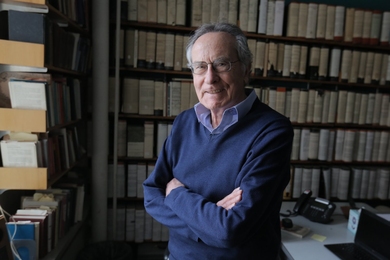

So while material needs matter, self-assessments about being “savers” or “spenders” do “a phenomenally good job of separating those who save from those who don’t,” says Jonathan Parker, the MIT economist who authored the study. “It’s a question about impatience. Are you someone who is impatient? If you get ‘yes’ for that answer, those are the spenders.”

The study bears on larger matters of both personal finance and tax policy, since the distribution of tax refunds by income bracket, for example, is tied to their overall economic impact. Like other research, the study shows that people lacking considerable income or wealth are more likely to spend such refunds more quickly.

“It does suggest that lower-income, lower-liquidity folks tend to tie their consumer demand very much to income,” says Parker, the Robert C. Merton Professor of Finance at the MIT Sloan School of Management.

The paper, “Why Don’t Households Smooth Consumption? Evidence from a $25 Million Experiment,” appears this month in the latest issue of the American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics.

Spend now: Three times as much, in fact

To conduct the study, Parker took advantage of a quirk in the 2008 stimulus. The federal government sent the payments to households on a schedule determined by the last two digits of the recipients’ social security number, something that is unrelated to financial circumstances or personal characteristics. Therefore the timing of the receipt of payments — and the subsequent spending that resulted — was effectively random.

All told, the study encompasses about 29,000 households actively participating in the Nielsen Consumer Panel, an ongoing survey that measures spending habits and household characteristics across the U.S. The average payment was around $900 per household.

On one level, the research reinforces the idea that basic financial need drives a certain portion of the household spending. On average, household spending on household goods rose by 10 percent the first week after the payment arrived, and by roughly 5 percent over the first four weeks. But households with low liquidity, which comprised 36 percent of those surveyed, spent more than three times as much of the money in the first week and more than twice as much of the payment in the first four weeks.

“There are people who have persistently lower incomes and lower liquidity, who spend this money when it arrives,” Parker says. Historical income performance was also bound up in this response. As Parker writes in the paper, “low income in 2006 is as good as” liquidity status at the same time, when it comes to “separating the households who spent from those who did not.”

Meanwhile, self-conception and long-run spending habits also influenced outcomes considerably, adding a wrinkle to existing models of household behavior in these circumstances. Parker’s research found that those who describe themselves as people who prefer to “spend now” rather than “save for the future” had a threefold increase in spending.

“I think it suggests to me there is a lot of heterogeneity on the preference side and the behavior side,” Parker says. “Despite the first-order importance of the financial variable in separating people, there’s also a lot of evidence that preferences matter a lot.”

Or, as he adds, “my findings are consistent with a reasonably simple model in which people with different degrees of impatience try to maintain a stable standard of living but face limits on low-cost borrowing. For the range of differences in behavior that I uncover, so-called behavioral modeling assumptions are second order.”

Research implications

The income distribution of any federal income tax cut or refund is an inherently political matter, and the outcome of current efforts in Washington to pass new tax legislation is uncertain. But regardless of policy outcomes, economists can continue to adjust their own models of consumer behavior based on new empirical findings.

Such models can also better inform the scoring of tax changes, as well as other models of policy, such as those used by the Federal Reserve to characterize how households respond to movements in interest rates.

In this vein, Parker’s study joins a growing body of literature (including some of his own previous work) that modifies the most streamlined models in which people smooth out consumption in anticipation of drops or increases in income — and instead accounts for the bumps and jolts in spending that the data reveals.

“We think that people try to maintain a reasonably stable standard of living,” Parker says. And yet, he notes, people “do an awful lot of spending when money shows up.”

In research terms, Parker says, one contribution of the study is to “cleanly identify and connect differences in spending behavior across people, to measureable differences in people,” such as their self-conceptions as “spenders” or “savers.” He hopes his work will pave the way for improved mathematical models of “consumption and savings and borrowing decisions that incorporate, in a simple yet rigorous way, these differences in behavior.”