When animals hunt or forage for food, they must constantly weigh whether the chance of a meal is worth the risk of being spotted by a predator. The same conflict between cost and benefit is at the heart of many of the decisions humans make on a daily basis.

The ability to instantly consider contradictory information from the environment and decide how to act is essential for survival. It’s also a key feature of mental health. Yet despite its importance, very little is known about the connections in the brain that give us the ability to make these split second decisions.

Now, in a paper published in the journal Nature Neuroscience, researchers at the Picower Institute for Learning and Memory at MIT reveal the circuit in the brain that is critical for governing how we respond to conflicting environmental cues.

Two regions of the brain — the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala and the medial prefrontal cortex — have for some time been implicated in reward-seeking and fear-related responses, according to Kay Tye, an assistant professor in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at MIT and a member of the Picower Institute for Learning and Memory. Tye is the senior author of the research, alongside post docs Anthony Burgos-Robles and Eyal Kimchi, who co-led the study.

“The amygdala is thought to be important for emotive processes, and the prefrontal cortex is thought to be important for higher cognitive processes,” Tye says. “So if I am walking down the street and a dog barks at me, my amygdala might respond immediately as I feel fear, but then I would see that the dog is chained up, and my prefrontal cortex could help to silence my amygdala.”

However, exactly how these two regions interact, and how information flows between the two structures to coordinate behavior in the face of competing signals has remained unclear, she says.

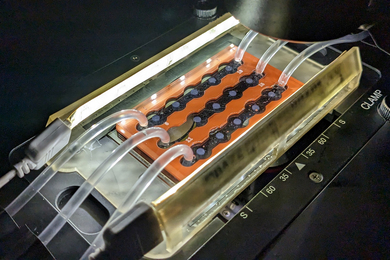

To better understand the mechanisms governing this process, the researchers simultaneously recorded the activity of neurons in both the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala (BLA) and the prelimbic (PL) medial prefrontal cortex in rats.

The researchers first tagged each set of neurons with a light-sensitive protein called channelrhodopsin.

The rats were then given a task to perform, in which they were presented with competing environmental signals: one associated with a sugary reward, and the other with a punishment. Then, when the researchers shone a light on the two regions of the brain, they were able to identify which neurons in the BLA were sending messages to the PL.

The researchers then investigated how accurately the firing of these neurons could predict how the animal would behave in the face of conflicting environmental cues.

They trained a machine-learning algorithm using data on how the neurons fired when the rats were presented with just the reward cue or the fear cue alone. They then tested the algorithm on data from the competition task, in which the rats were presented with both cues simultaneously.

“We found that the BLA neurons that connect directly to the PL performed much better than other BLA neurons and other PL neurons, in predicting the behavior of the animals during competition,” Tye says.

This suggests that whatever information is transmitted from the BLA to the PL can predict how the animal will act. “The routing of information from the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala to the prefrontal cortex is critical for decision-making during conflict,” Tye says.

This is important, because the ability to make good decisions when there is conflict is a fundamental one, she says: “All the time we are being presented with positive and negative cues, and a lot of the time it is up to us to determine what we respond to.”

The findings could also have implications for our understanding of mental illness, since people with a psychiatric disorder may not always be capable of making good judgments.

The study shows that researchers should make every effort to understand how several regions control a complex behavior, according to Rony Paz, an associate professor in neurobiology at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, who was not involved in the research.

“Taken together with previous studies, the paper shows that maladaptive abnormal behaviors, such as in anxiety disorders, are a result of imbalances in the subcortical-cortical circuitry,” Paz says. “But unlike the classical concepts, we now know better that both sides of the equation (circuit) need to be controlled and normalized in order to restore normal function.”

The researchers now hope to collaborate with other teams to develop a computational model of how the two areas of the brain carry out the process of decision-making during conflict. This model could then be tested, to learn more about the mechanisms involved.