For centuries, cellulose has formed the basis of the world’s most abundantly printed-on material: paper. Now, thanks to new research at MIT, it may also become an abundant material to print with — potentially providing a renewable, biodegradable alternative to the polymers currently used in 3-D printing materials.

“Cellulose is the most abundant organic polymer in the world,” says MIT postdoc Sebastian Pattinson, lead author of a paper describing the new system in the journal Advanced Materials Technologies. The paper is co-authored by associate professor of mechanical engineering A. John Hart, the Mitsui Career Development Professor in Contemporary Technology.

Cellulose, Pattinson explains, is “the most important component in giving wood its mechanical properties. And because it’s so inexpensive, it’s biorenewable, biodegradable, and also very chemically versatile, it’s used in a lot of products. Cellulose and its derivatives are used in pharmaceuticals, medical devices, as food additives, building materials, clothing — all sorts of different areas. And a lot of these kinds of products would benefit from the kind of customization that additive manufacturing [3-D printing] enables.”

Meanwhile, 3-D printing technology is rapidly growing. Among other benefits, it “allows you to individually customize each product you make,” Pattinson says.

Using cellulose as a material for additive manufacturing is not a new idea, and many researchers have attempted this but faced major obstacles. When heated, cellulose thermally decomposes before it becomes flowable, partly because of the hydrogen bonds that exist between the cellulose molecules. The intermolecular bonding also makes high-concentration cellulose solutions too viscous to easily extrude.

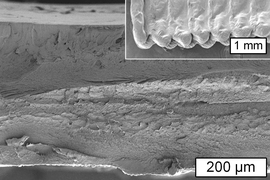

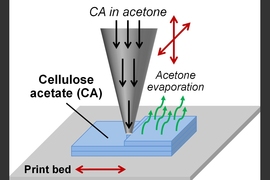

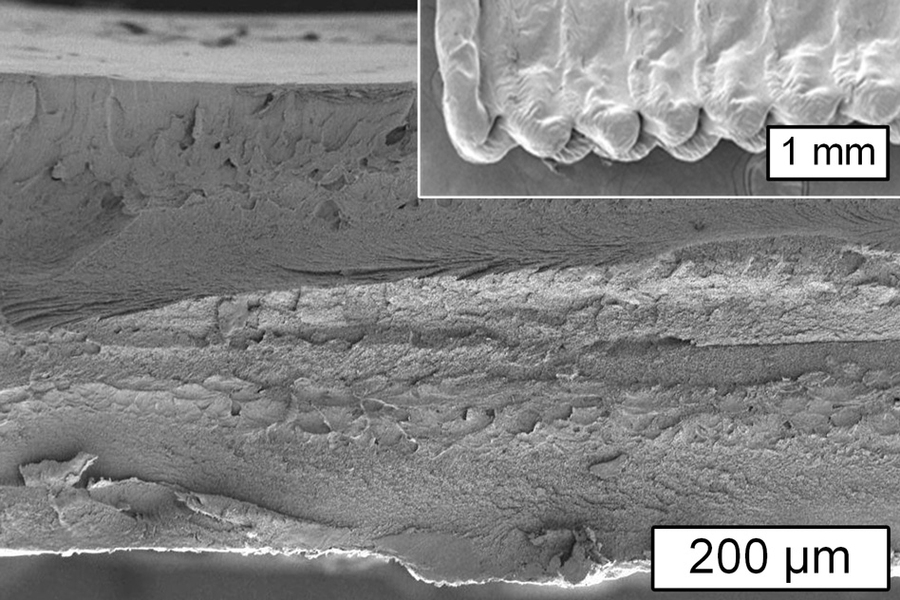

Instead, the MIT team chose to work with cellulose acetate — a material that is easily made from cellulose and is already widely produced and readily available. Essentially, the number of hydrogen bonds in this material has been reduced by the acetate groups. Cellulose acetate can be dissolved in acetone and extruded through a nozzle. As the acetone quickly evaporates, the cellulose acetate solidifies in place. A subsequent optional treatment replaces the acetate groups and increases the strength of the printed parts.

“After we 3-D print, we restore the hydrogen bonding network through a sodium hydroxide treatment,” Pattinson says. “We find that the strength and toughness of the parts we get … are greater than many commonly used materials” for 3-D printing, including acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) and polylactic acid (PLA).

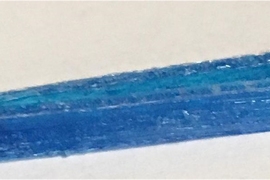

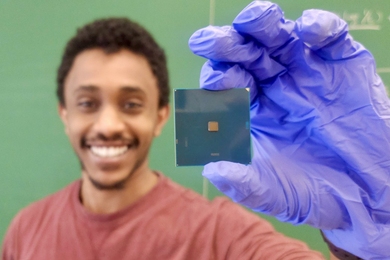

To demonstrate the chemical versatility of the production process, Pattinson and Hart added an extra dimension to the innovation. By adding a small amount of antimicrobial dye to the cellulose acetate ink, they 3-D-printed a pair of surgical tweezers with antimicrobial functionality.

“We demonstrated that the parts kill bacteria when you shine fluorescent light on them,” Pattinson says. Such custom-made tools “could be useful for remote medical settings where there’s a need for surgical tools but it’s difficult to deliver new tools as they break, or where there’s a need for customized tools. And with the antimicrobial properties, if the sterility of the operating room is not ideal the antimicrobial function could be essential,” he says.

Because most existing extrusion-based 3-D printers rely on heating polymer to make it flow, their production speed is limited by the amount of heat that can be delivered to the polymer without damaging it. This room-temperature cellulose process, which simply relies on evaporation of the acetone to solidify the part, could potentially be faster, Pattinson says. And various methods could speed it up even further, such as laying down thin ribbons of material to maximize surface area, or blowing hot air over it to speed evaporation. A production system would also seek to recover the evaporated acetone to make the process more cost effective and environmentally friendly.

Cellulose acetate is already widely available as a commodity product. In bulk, the material is comparable in price to that of thermoplastics used for injection molding, and it’s much less expensive than the typical filament materials used for 3-D printing, the researchers say. This, combined with the room-temperature conditions of the process and the ability to functionalize cellulose in a variety of ways, could make it commercially attractive.

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation.