A team of MIT students and alumni won the MIT Clean Energy Prize (CEP) competition on Saturday for creating a “brain” for microgrids, which are smaller, localized versions of traditional power grids. The technology makes the systems more efficient and easier to own and operate.

The team, Heila Technologies, beat out five other finalist teams at the ninth annual CEP, held in Kresge Auditorium, to take home the $100,000 Grand Prize, presented by National Grid. Heila has developed a universal control hub that automatically monitors and manages disparate microgrids — such as those that power solar panels, wind turbines, and gas generators — at places like company campuses, military bases, and rural villages, for optimal performance.

By simplifying microgrids, Heila aims to boost their adoption worldwide, said team member John Donnal, a PhD student in electrical engineering and computer science. “A big problem we’ve seen in microgrids is, when you buy them, you can’t get them to work together,” Donnal said. “Now you, as a customer, can go out and find the best industry player to get the [microgrid] equipment, and you get Heila to get them to all talk to each other. And when you can make microgrids that easy, you can then integrate renewables at a much higher rate.”

Heila has already generated $95,000 in revenue from months of piloting its controllers at a vineyard in Sonoma County in California, where it integrates gas generators and hundreds of solar panels connected to multiple types of batteries.

With the CEP prize money, Heila plans to start implementing its technology at military bases and in off-grid regions, said Heila team member Jorge Elizondo, a PhD student in electrical engineering and computer science at MIT. “This will help us hire people and move faster in expansion, which is critical in this space,” he said.

Big winners

As the nation’s largest energy-innovation competition for students from universities around the nation, the CEP has dished out more than $2.6 million to help launch clean-energy startups since its founding in 2008. Past teams have collectively raised more than $430 million in additional financing after competition, and have employed more than 700 people around the globe.

This year, around 70 teams submitted applications for the competition, and 17 were selected to showcase their ideas to judges and attendees on Saturday, including seven from MIT. Six finalist teams were then chosen to compete for $225,000 in prizes in three categories: renewable energy, energy efficiency, and infrastructure and resources.

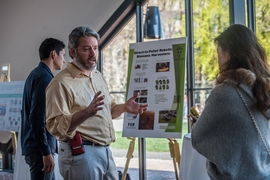

Iron Goat, a team from George Mason University, was also a big winner on Saturday, capturing both the renewable-energy prize for $20,000 and a $50,000 prize from the Department of Energy. Iron Goat is developing a robotic hay compactor that can produce yields at one-third the cost of traditional bailing methods, and generates its own fuel from the biomass harvested.

Two other teams earned $20,000 each for winning their respective tracks: A Northwestern University team, Amper, won in the energy efficiency category, for developing an app that monitors electricity usage of smart appliances, to save home owners on annual utilities costs; and Poly6, an MIT team, won in the infrastructure and resources category, for making a clean and sustainable bioplastic product out of citrus rinds.

Additionally, Qapture, from Colorado State University, won a $15,000 energy development prize, for making a device that converts waste heat from chimney cook stoves into electrical power while reducing stove emissions by up to 90 percent.

In her welcoming remarks, Sally Lambert, an MIT Sloan School of Management student who co-manages the competition with classmate Ryan Macpherson, said the competition’s aim “is to inspire and prepare the next generation of clean-energy entrepreneurs to go out and tackle those huge, pressing energy problems in our world today.”

Keynote speakers were Adam Cohen, deputy under secretary for science and energy at the Department of Energy, and Paul Bodnar, senior director for energy and climate change at the National Security Council.

Simplifying microgrids

Microgrids integrate well with renewable energy sources, including solar and wind power, small hydroelectric power, geothermal energy, and waste-to-energy systems. In 2014, the global microgrid market raked in $4.3 billion in revenue, and it could hit $36 billion by 2020, according to a 2015 report by Navigant Research, a market research and consulting firm.

However, microgrids are complex and nonstandardized systems, so it’s sometimes difficult to manage multiple types of microgrids — or even one type — and it usually requires hiring a professional engineer to implement any modifications to the systems. “This is because every single piece of equipment speaks a different language,” Elizondo said.

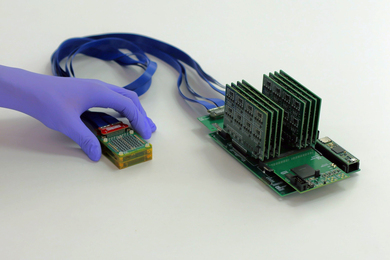

So the Heila team developed software, called Heila IQ, to integrate the languages of all microgrid systems into a platform in the cloud. Microgrid managers can monitor and control all the microgrids through the control hub — which resembles a circuit breaker box — installed somewhere nearby. The hubs sense changes in each system’s conditions, react to the changes, and learn from the long-term operation of the microgrid to improve performance.

Heila IQ is also an open platform in the cloud, meaning Web developers can potentially develop apps for Heila’s controllers. “You can deploy apps on your microgrid in the same that you look at apps on your phone, but for things like [microgrid] management and diagnostics,” Donnal said.