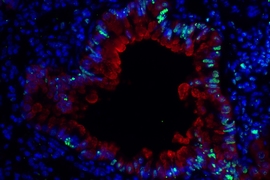

House dust mites, which are a major source of allergens in house dust, can cause asthma in adults and children. Researchers from MIT and the National University of Singapore have now found that these mites have a greater impact than previously known — they induce DNA damage that can be fatal to lung cells if the damaged DNA is not adequately repaired.

The findings suggest that DNA repair capacity, which varies widely among healthy individuals, could be a susceptibility factor that places an asthmatic patient at increased risk of developing asthma-associated pathologies, the researchers say.

“DNA damage is a component in asthma development, potentially contributing to the worsening of asthma. In addition to activation of immune responses, patients’ DNA repair capacity may affect disease progression,” says Bevin Engelward, a professor of biological engineering at MIT and a senior author of the study. “Ultimately, screening for DNA repair capacity might be used to predict the development of severe asthma.”

Fred Wong Wai-Shiu, head of the Department of Pharmacology at the National University of Singapore, is also a senior author of the study, which appears in the May 1 issue of the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. The paper’s lead author is Tze Khee Chan, a graduate student in the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology (SMART).

Beyond asthma

Asthma is usually triggered by an exaggerated immune response to allergens such as dust mites, pollen, or pet dander. Immune cells flood the lung where the allergen has invaded, secreting immune chemicals called cytokines that drive inflammation and constriction of the smooth muscle, leading to narrowing of the airways and making breathing difficult. More than 300 million people suffer from asthma worldwide, and in the United States about 8 percent of the population is affected.

The research team focused on dust-mite-induced allergies because dust mites are ubiquitous and thrive in warm, humid climates. Dust mites provoke allergic symptoms, such as sneezing and watery eyes, and in sensitive individuals dust mites can even trigger allergic asthma. Up to 85 percent of patients with asthma are allergic to dust mites, making it the main trigger for allergic asthma.

When the researchers exposed mice to dust mites, to induce an asthma-like condition, they found an alternative pathway that contributes to asthma development. In these mice, the dust mites caused production of chemicals called reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS), which are known for their potential to damage DNA and other biological molecules.

Furthermore, when DNA repair is inhibited using a drug called NU7441, more DNA damage and cell death are observed. There is a wide range of DNA repair capacity among people, so the findings suggest that asthma patients with poor DNA repair capacity could be more susceptible to asthma-induced inflammation and tissue damage.

Predicting and preventing damage

Although the mechanism is not known, dust mites can also directly induce DNA damage when they come into contact with cultured human cells.

“Our findings show that dust mites can not only induce an immune response, they can also cause direct DNA damage in the lung epithelial cells. These damaging effects are magnified when DNA repair is inhibited. It shows how important DNA repair is to prevent cell death,” Chan says.

“Our current understanding is that inflammatory cells, such as eosinophils, neutrophils, and macrophages, produce free radicals that damage the cell. But right now what we observe is the epithelial cell by itself, without the other cells, can actually produce free radicals when exposed to dust mites. This is a finding that has not been reported before,” Wong says.

The findings provide additional data to support the possibility of treating asthma patients with antioxidants to neutralize the RONS, in order to help prevent asthma-induced tissue damage. The researchers are now testing this approach in mice.

“This important report suggests that a paradigm shift may now be in order for allergens as environmental agents, and also for our understanding of the steps by which inhaled allergens interact with the lung to induce allergic asthma,” says Michael Fessler, a senior investigator at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, who was not involved in the research.

Finally, the results suggest that DNA damage may also be an important underlying factor in asthma exacerbation caused by inflammation during infectious diseases such as rhinovirus infection, the researchers say.

The research was funded by the National Medical Research Council of Singapore and the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology (SMART).