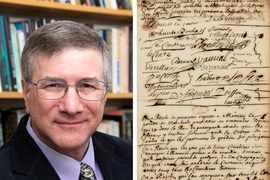

A couple of centuries from now, will anyone remember the hit Broadway show “Hamilton?” Will they know how popular it was? As it happens, historians do know a great deal about Enlightenment-era French theater, and they continue to learn more — thanks in part to the Comédie Française Registers Project (CFRP), an ongoing effort led by Jeffrey Ravel, head of the MIT History faculty. Ravel and his colleagues have digitized over 100 years of theater records to learn more about the intersection of popular culture, politics, and social life during the 17th and 18th centuries. Now MIT is co-hosting (along with Harvard University’s Department of Romance Languages and Literatures) a global conference on the subject, being held May 19-21. Ravel sat down to talk with MIT News.

Q. What is the Comédie Française Registers Project?

A. The Comédie Française Registers Project is based on archival documents from the late 17th and 18th centuries. The Comédie Française was and still is the primary state-funded theater troupe in France. It was founded by Louis XIV, the “Sun King,” in 1680; took a brief hiatus [from 1793-1799] during the French Revolution; was reconstituted by Napoleon; and continues to exist today. Our project covers the troupe’s nightly box-office receipt records from 1680 until 1793 — over 34,000 performances. We have created high-resolution digital images of each page, extracted the box office data from the registers, compiled it in a searchable database, and created search and visualization tools to interrogate the data. These tools allow us to see what kinds of trends emerge about the popularity of plays, playwrights, contemporary political themes, and various aspects of the repertory.

The Paris theater records were absolutely unique in this time. London had a very vibrant theater scene, but the English did not keep these kinds of detailed box-office records until late in the 18th century. In France, the Roman Catholic church insisted that the actors in Paris, who enjoyed a privilege [permission] from the king to perform the plays, pay a sort of sin tax, which amounted to about one-sixth of every evening’s proceeds. This share of the nightly receipts went to charitable organizations. Because the church had the crown levy this penalty, the government forced the actors to keep very precise records, which is a good thing for us!

The Comédie Française was also an incredibly democratic organization in a divine-right monarchy where there were few egalitarian institutions. By this I mean that the troupe was run jointly by its members, each of whom received a full share of each evening’s proceeds, a half share, or a quarter share, depending on seniority and celebrity status. A subcommittee of the actors was responsible for accepting new plays into the repertory and scheduling performances. There were no artistic directors or general managers, although the king assigned members of his court to oversee the troupe’s activities.

Q. What have you learned from the project so far?

A. Even at this early stage, a few insights have emerged. While some literary scholars have settled on a few key names as being representative of theatrical production in the 17th and 18th centuries — Moliere, Pierre Corneille, Racine, Voltaire — the Comédie Française repertory consisted of more than 1,200 plays, authored by more than 300 playwrights. Now, some of those plays were probably not very good and deserved to fall into oblivion, but others were both financially and aesthetically successful and still have ways of speaking to us today. So not only have historians and theater studies specialists and literature scholars been interested in the project, but people who are performing plays in the Francophone world today have been intrigued to learn there are more plays that might be worth reviving.

The common assumption is that the theater became more politicized on the eve of the French Revolution, and the classic example is Beaumarchais’ “The Marriage of Figaro,” which premiered at the Comédie Française in 1784 and had the longest first run of any play in the century. It contains some highly politicized scenes. But light comedies also did well throughout the period, as did a new generation of sentimental dramas in the period before 1789. Theater, like many human activities, is multifaceted. Some people went to the theater because the playhouse provided a public forum for discussing the new ideas of the Enlightenment and concepts that would influence the revolutionaries after 1789. But other people went to the theater just to blow off steam and enjoy themselves.

We are still trying to understand the economics of theater-going over the course of these 113 years. For example, we have limited records about the casting of plays, but we have already recognized that when new actors or actresses debuted, there would be spikes in attendance. Some of my colleagues are interested in adding the data from [the post-1799 period] when the troupe was reconstituted by Napoleon.

Q. How does the conference relate to the Comédie Française Registers Project?

A. We will devote about 1 ½ days to traditional academic presentations and discussions of papers based on analysis of the database. We’re also going to be pairing the scholars with database developers, so they can work together to build tools that respond to scholarly or pedagogical needs.

With the MIT Press, we are generating a prototype for an online text of the conference proceedings that will allow scholars to publish their papers online and to embed the search and visualization tools we’ve developed on the website. I think intellectual and cultural historians who are willing to consider quantitative approaches have a great deal to learn from projects such as this one. Having said that, I see the digital humanities and quantitative approaches as being one methodology among many that historians have for years, or in some cases decades, been using profitably. These analytical tools give us insights we can situate in the context of what we know. We’re not going to discard the work that has been done, but technology can enhance traditional humanities methods in ways that lead to new conclusions — and new questions.

![“I was always very interested in current events and fascinated by what was happening in the world around me,” MIT historian Tanalís Padilla says. “My parents were very political. I considered myself quite a political being. … I think [living in] Mexico and the United States and seeing the contrast to be so great, especially in rural Mexico, made me aware [of politics] early on.”](/sites/default/files/styles/news_article__archive/public/images/201601/MIT-Tanalis-Padilla_0.jpg?itok=_0JZLf10)