Dutch artist Theo Jansen and two of his Strandbeests visited the MIT Media Lab on Sept. 10, for the first “ML Talk” of the fall 2015 semester, “Theo Jansen in conversation with Neri Oxman and Trevor Smith.”

Jansen’s Strandbeests — “beach animals” in Dutch — seem more like evolutionary inevitabilities than one artist’s brainchildren. Jansen engineers wondrous, large-scale kinetic sculptures from humble PVC tubing and endows them with the ability to harness available and stored wind power for their locomotion. For the past 20 years, Jansen has been perfecting his Strandbeest designs on Scheveningen Beach on the Dutch seaside, while gaining international recognition.

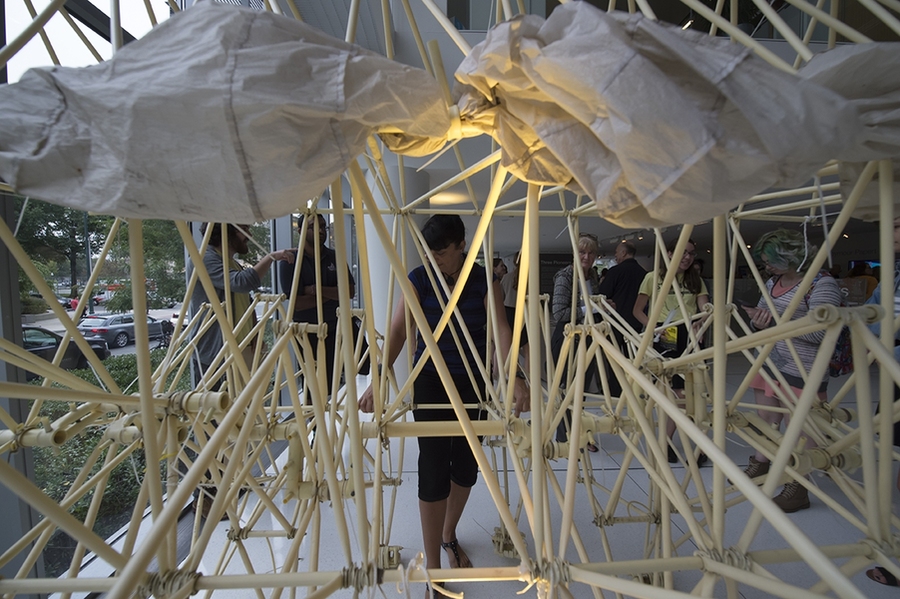

Audience members at the Media Lab had the opportunity to interact with two examples of "Animaris Ordis" — Jansen borrows Carl Linnaeus’s binomial nomenclature for his Strandbeests — before hearing from the artist himself. When Jansen took the stage, he instantly charmed the MIT audience, stating, “I feel honored to be at the center of the brain of the world.” A trained physicist, he became a painter before focusing his attention on sculptural works. He first came to prominence in 1980 when he flew a "UFO" — made of plastic sheeting on a light frame — across the skies of Delft, Holland.

Motivated by concern for the erosion along the Dutch coast, he wrote a 1990 column in De Volkskrant in which he speculated that robots will be needed to redistribute sand to the dunes. Months later, he bought some PVC tubing and resolved to devote one year to realizing this project. He has been involved in “passive robotics,” or “kinetic sculpture,” ever since.

Much of his talk focused on the Strandbeests’ mesmerizing leg systems. Resembling animate animal skeletons, each type of “beest” has its own gait. Jansen showed a video of the sculptures galloping and trotting along the seaside, after which the audience erupted into applause. With each successive iteration, he refines the design; some have sails, or shovel arms, others have fanlike blades that pump air into plastic bottles for pressurized storage, or sensors to detect when it is in or near water, or hammers to anchor itself to the beach to weather storms. Jansen was modest about his creative limits, saying, “I didn’t create the movement. I created the leg mechanism. I just used mechanics.” The Strandbeests’ poetic movement surprised even him.

Of particular interest to the engineers and roboticists in the crowd, Jansen shared the story of the mechanical breakthrough that has made his work possible. On a sleepless night in 1991, he figured out the genetic algorithm for the leg design, which led to the “beest” being able to propel itself forward without a third limb, as his previous more complicated design required: “The crank shaft slowly came from infinity toward the beest, to the leg. It turns out that the angle is more or less 90 degrees,” he indicated on a model of the leg mechanism. “A few hours later,” he continued, “I realized I had to write the genetic algorithm to define the length of the tubes, so it would lift off the ground itself and wouldn’t need a third limb anymore.”

He published this “DNA code” of the Strandbeests on his website, and thousands of students started making — and even 3-D printing — “beests” of all sizes. Jansen welcomes this kind of imitation, declaring with mock-seriousness that while the students think they are enjoying a new hobby, they are, in fact, being cleverly “used for the reproduction of the Strandbeests.”

It is not only Jansen who imputes animal consciousness to his elaborate PVC constructions. During the panel discussion with Trevor Smith, curator of the Present Tense initiative at the Peabody Essex Museum; Neri Oxman, the Sony Corporation Career Development Associate Professor of Media Arts and Sciences at the MIT Media Lab; and photographer Lena Herzog following Jansen’s talk, Smith spoke of how he routinely witnesses museum visitors forming “empathic relationships” with the Strandbeests. Jansen attributes this behavior to the sculptures’ animal-like appearance: “It’s hard to find an animal which is not fascinating to look at because you read the history and evolution of the animal into it, and that somehow appeals to our sense of beauty.” Herzog, whose photographs testify to her longtime fascination with Jansen’s work, shared her insights into the work’s mass appeal: “I think certain things that enchant us have many hooks into us. And the wider the range of these hooks, or references, the more they hold onto us.” Jansen’s work frequently draws comparisons to sketches by Leonardo da Vinci, and paintings or sculptures by Italian futurists and surrealists. Yet the Strandbeests present enough other “hooks,” Herzog points out, to enchant even viewers without knowledge of sophisticated art references — children, dogs, horses; they captivate all who encounter them.

The event culminated in an outdoor demonstration of the "Animaris Ordis" walking on a paved area beside the Media Lab, with Jansen himself rallying volunteers to walk and run with the Strandbeest. The diversity of the onlookers in this Cambridge audience confirmed Herzog’s analysis — that young and old alike were fascinated by seeing the “beest” in motion, and equally enthralled by its maker.

This visit to MIT was one of several preview events for “Strandbeest: The Dream Machines of Theo Jansen,” the first major U.S. exhibition of Jansen’s work, which opens at the Peabody Essex Museum on Sept. 19. The exhibition features six Strandbeests, as well as the artist’s drawings, demonstrations of the creatures' complex ambulatory systems, a hall of "fossils," and photography by Lena Herzog. Smith commented that introducing the exhibition at the Media Lab struck him as “natural fit,” for Jansen’s dynamic and interdisciplinary work blurs the lines between art and engineering, and appeals to engineers, biologists, philosophers, environmentalists, makers and artists alike. Smith also noted that designers in the Media Lab have collaborated with PEM to create its makerspace, and the relationship between the two institutions is continuously expanding.