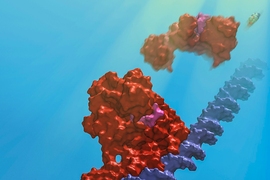

MIT scientists, working with colleagues in Spain, have discovered and mapped a light-sensing protein that uses vitamin B12 to perform key functions, including gene regulation.

The result, derived from studying proteins from the bacterium Thermus thermophilus, involves at least two findings of broad interest. First, it expands our knowledge of the biological role of vitamin B12, which was already understood to help convert fat into energy, and to be involved in brain formation, but has now been identified as a key part of photoreceptor proteins — the structures that allow organisms to sense and respond to light.

Second, the research describes a new mode of gene regulation, in which the light-sensing proteins play a key role. In so doing, the scientists observe, the bacteria have repurposed existing protein structures that use vitamin B12, and put them to work in new ways.

“Nature borrowed not just the vitamin, but really the whole enzyme unit, and modified it … and made it a light sensor,” says Catherine Drennan, a professor of chemistry and biology at MIT.

The findings are detailed this week in the journal Nature. The paper describes the photoreceptors in three different states: in the dark, bound to DNA, and after being exposed to light.

“It’s wonderful that we’ve been able to get all the series of structures, to understand how it works at each stage,” Drennan says.

The paper has nine co-authors, including Drennan; graduate students Percival Yang-Ting Chen, Marco Jost, and Gyunghoon Kang of MIT; Jesus Fernandez-Zapata and S. Padmanabhan of the Institute of Physical Chemistry Rocasolano, in Madrid; and Monserrat Elias-Arnanz, Juan Manuel Ortiz-Guerreo, and Maria Carmen Polanco, of the University of Murcia, in Murcia, Spain.

The researchers used a combination of X-ray crystallography techniques and in-vitro analysis to study the bacteria. Drennan, who has studied enzymes that employ vitamin B12 since she was a graduate student, emphasizes that key elements of the research were performed by all the co-authors.

Jost performed crystallography to establish the shapes of the structures, while the Spanish researchers, Drennan notes, “did all of the control experiments to show that we were really thinking about this right,” among other things.

By studying the structures of the photoreceptor proteins in their three states, the scientists developed a more thorough understanding of the structures, and their functions, than they would have by viewing the proteins in just one state.

Microbes, like many other organisms, benefit from knowing whether they are in light or darkness. The photoreceptors bind to the DNA in the dark, and prevent activity pertaining to the genes of Thermus thermophilus. When light hits the microbes, the photoreceptor structures cleave and “fall apart,” as Drennan puts it, and the bacteria start producing carotenoids, which protect the organisms from negative effects of sunlight, such as DNA damage.

The research also shows that the exact manner in which the photoreceptors bind to the DNA is novel. The structures contain tetramers, four subunits of the protein, of which exactly three are bound to the genetic material — something Drennan says surprised her.

“That’s the best part about science,” Drennan says. “You see something novel, then you think it’s not really going to be that novel, but you do the experiments [and it is].”

Other scientists say the findings are significant. “It’s a very exciting development,” says Rowena Matthews, a professor emerita of biological chemistry at the University of Michigan, who has read the paper. Of the newly discovered use of vitamin B12 and a derivative of it, adenosylcobalamin, Matthews adds, “There was very limited knowledge of its versatility.”

Drennan adds that in the long run, the finding could have practical applications, such as the engineering of light-directed control of DNA transcription, or the development of controlled interactions between proteins.

“I would be very interested in … thinking about whether there could be practical applications of this,” Drennan says.