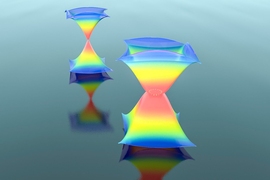

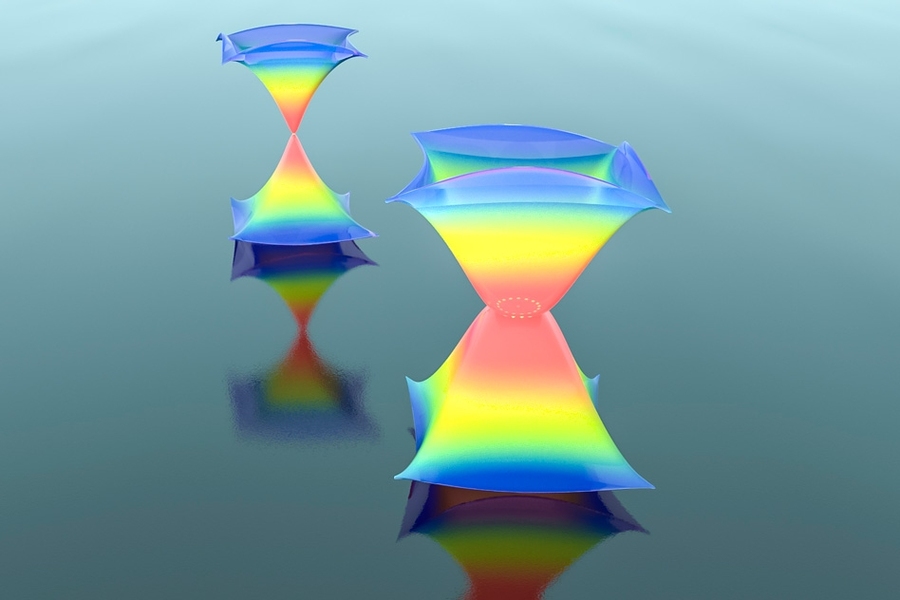

The Dirac cone, named after British physicist Paul Dirac, started as a concept in particle and high-energy physics and has recently became important in research in condensed matter physics and material science. It has since been found to describe aspects of graphene, a two dimensional form of carbon, suggesting the possibility of applications across various fields.

Now physicists at MIT have found another unusual phenomenon produced by the Dirac cone: It can spawn a phenomenon described as a “ring of exceptional points.” This connects two fields of research in physics and may have applications in building powerful lasers, precise optical sensors, and other devices.

The results are published this week in the journal Nature by MIT postdoc Bo Zhen, Yale University postdoc Chia Wei Hsu, MIT physics professors Marin Soljačić and John Joannopoulos, and five others.

This work represents “the first experimental demonstration of a ring of exceptional points,” Zhen says, and is the first study that relates research in exceptional points with the physical concepts of parity-time symmetry and Dirac cones.

Individual exceptional points are a peculiar phenomenon unique to an unusual class of physical systems that can lead to counterintuitive phenomena. For example, around these points, opaque materials may seem more transparent, and light may be transmitted only in one direction. However, the practical usefulness of these properties is limited by absorption loss introduced in the materials.

The MIT team used a nanoengineered material called a photonic crystal to produce the exceptional ring. This new ring of exceptional points is different from those studied by other groups, making it potentially more practical, the researchers say.

“Instead of absorption loss, we adopt a different loss mechanism — radiation loss — which does not affect the device performance,” Zhen says. “In fact, radiation loss is useful and is necessary in devices like lasers.”

This phenomenon could enable creation of new kinds of optical systems with novel features, the MIT team says.

“One important possible application of this work is in creating a more powerful laser system than existing technologies allow,” Soljačić says. To build a more powerful laser requires a bigger lasing area, but that introduces more unwanted “modes” for light, which compete for power, limiting the final output.

“Photonic crystal surface-emitting lasers are a very promising candidate for the next generation of high-quality, high-power compact laser systems,” Soljačić says, “and we estimate we can improve the output power limit of such lasers by a factor of at least 10.”

“Our system could also be used for high-precision detectors for biological or chemical materials, because of its extreme sensitivity,” Hsu says. This improved sensitivity is due to another exotic property of the exceptional points: Their response to perturbations is not linear to the perturbation strength.

Normally, Hsu says, it becomes very difficult to detect a substance when its concentration is low. When the concentration of the target substance is reduced by a million times, the overall signal also decreases by a million times, which can make it too small to detect.

“But at an exceptional point, it’s not linear anymore,” Hsu says, “and the signal goes down by only 1,000 times, providing a much bigger response that can now be detected.”

Demetrios Christodoulides, a professor of optics and photonics at the University of Central Florida who was not involved in this work, says, “This represents the first observation of an exceptional ring in a 2-D crystal associated with a two-dimensional band. The MIT work opens up a number of opportunities … in particular, around exceptional points where systems are known on many occasions to behave in a peculiar fashion.”

The research team also included Yuichi Igarashi of NEC Corp. in Japan and MIT research scientist Ling Lu, postdoc Ido Kaminer, Harvard University graduate student Adi Pick, and Song-Liang Chua at DSO National Laboratory in Singapore. The work was supported, in part, by the Army Research Office through MIT’s Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies, the National Science Foundation, and the Department of Energy.