When Lt. Col. Consuelo Castillo Kickbusch, the daughter of a maid and a handyman, was growing up in a barrio in Laredo, Tex., the helping hand of a big-hearted stranger helped her to dream of a better life — and to reach for it. Years later, thanks to the help of a Mr. Cooper from South Boston, she said, she went on to a distinguished 20-year career in the U.S. Army, becoming the first female commissioned officer in Texas and commanding three units of soldiers.

Kickbusch, the keynote speaker at this year’s MIT Diversity Summit, said she later left the Army to carry out a mission to inspire others like her who may not have good role models, or who may not be taken seriously because of their color, sex, ethnicity, or religion.

“I feel like I’ve met a soulmate,” said physics professor Edmund Bertschinger, who was named last year as MIT’s first Institute Community and Equity Officer, in his introduction of Kickbusch. They share a vision of meritocracy and diversity, he said, “because good ideas come from anyone, anywhere.”

Growing up, Kickbusch said, even her own mother gave her a clear impression that “I didn’t have the same value as my brothers, all seven of them.”

Looking back on her childhood, she wondered, “Does MIT have a space for a kid like me?” The answer, she said, from the aims expressed by President L. Rafael Reif and by the Diversity Summit, is an emphatic yes. The question, she added, is how to make sure talented youngsters are aware of the possibilities and encouraged to pursue them.

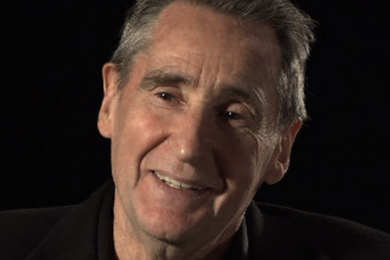

For Kickbusch, that’s where “Mr. Cooper” came in. “Many of us are here because someone said, ‘I believe in you,’” she said. “The person who saved my life was a professor from South Boston.” He left a tenured position, she said, in order “to create change himself. He came to the barrio.”

Offering to help Kickbusch and her siblings get a better start in life, he began by giving them standardized tests. “My first test scores showed, on paper, I was retarded,” she said. But her mentor, undaunted, took her to the local library, where a librarian began teaching her to read. After some time, he tested her again, and declared, “You can go to any university in the United States.”

Later, she asked Cooper why he had come to help her and others like her. “I was just a brown kid, I was supposed to be stupid, I was just a girl,” she said. He proceeded to talk about his own childhood, when he had a best friend in high school whose parents forbade them to spend time together. The reason: Cooper was Irish-American, and his friend was Italian-American. “We were just two white boys, just wanting to be friends,” he said. “I’m not just a white face,” he added. “I am you.”

The lesson, Kickbusch said: Never try to judge another’s experience based on superficialities. “Ask someone their story,” she urged.

Like Cooper, Kickbusch decided it was important to help others overcome obstacles and find success. “At the peak of my career, I laid my uniform down,” she said. Since then, she has created educational programs, written books about how to achieve success, and given talks and workshops around the country to inspire young people to take charge of their lives, and to strive for success in science and engineering.

“I ask you, I plead with you, come look for these kids,” Kickbusch said. “There are thousands of them.”

Kickbusch described a meeting with a California superintendent who said that she wanted to hire more minority teachers, but couldn’t find talented applicants. After a discussion with Kickbusch, it became clear that 18 people on the superintendent’s own staff wanted to complete college; some already had three years of college credit. She found ways to help them finish their degrees; now all 18 are employed as teachers in her district.

The key thing, Kickbusch said, is “looking out where we don’t normally look.”

Bertschinger, in closing remarks at the Diversity Summit’s opening session, urged the students, faculty, and staff in attendance to “share this vision with others. We’re the engine that’s going to drive change, in our Institute and in the nation.”

The Diversity Summit continues on Tuesday with a series of workshops, and on Wednesday with the screening of a documentary about civil rights leader Bayard Rustin.