More than 60 years ago, scientists discovered the underlying cause of sickle cell disease: People with the disorder produce crescent-shaped red blood cells that clog capillaries instead of flowing smoothly, like ordinary, disc-shaped red blood cells do. This can cause severe pain, major organ damage and a significantly shortened lifespan.

Researchers later found that the disease results from a single mutation in the hemoglobin protein, and realized that the sickle shape — seen more often in people from tropical climates — is actually an evolutionary adaptation that can help protect against malaria.

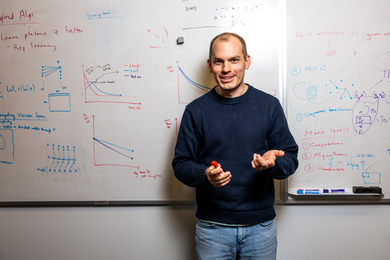

However, despite everything scientists have learned about the disease, which affects 13 million people worldwide, there are few treatments available. “We still don’t have effective enough therapies and we don’t have a good feel for how the disease manifests itself differently in different people,” says Sangeeta Bhatia, the John and Dorothy Wilson Professor of Health Sciences and Technology and Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at MIT.

Bhatia, MIT postdoc David Wood, and colleagues at Harvard University, Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and Brigham and Women’s Hospital have now devised a simple blood test that can predict whether sickle cell patients are at high risk for painful complications of the disease. To perform the test, the researchers measure how well blood samples flow through a microfluidic device.

The device, described March 1 in the journal Science Translational Medicine, could help doctors monitor sickle cell patients and determine the best course of treatment, Bhatia says. It could also aid researchers in developing new drugs for the disease.

Monitoring blood flow

Sickle cell patients often suffer from anemia because their abnormal red blood cells don’t last very long in circulation. However, most of the symptoms associated with the disease are caused by vaso-occlusive crises that occur when the sickle-shaped cells, which are stiffer and stickier than normal blood cells, clog blood vessels and block blood flow. The frequency and severity of these crises vary widely between patients, and there is no way to predict when they will occur.

“When a patient has high cholesterol, you can monitor their risk for heart disease and response to therapy with a blood test. With sickle cell disease, despite patients having the same underlying genetic change, some suffer tremendously while others don’t — and we still don’t have a test that can guide physicians in making therapeutic decisions,” Bhatia says.

In 2007, Bhatia and L. Mahadevan, a Harvard professor of applied mathematics who studies natural and biological phenomena, started working together to understand how sickle cells move through capillaries. In the current study, the researchers recreated the conditions that can produce a vaso-occlusive crisis: They directed blood through a microchannel and lowered its oxygen concentration, which triggers sickle cells to jam and block blood flow.

For each blood sample, they measured how quickly it would stop flowing after being deoxygenized. John Higgins of MGH and Harvard Medical School, an author of the paper, compared blood samples taken from sickle cell patients who had or had not made an emergency trip to the hospital or received a blood transfusion within the previous 12 months, and found that blood from patients with a less severe form of the disease did not slow down as quickly as that of more severely affected patients.

No other existing measures of blood properties — including concentration of red blood cells, fraction of altered hemoglobin or white blood cell count — can make this kind of prediction, Bhatia says. The finding highlights the importance of looking at vaso-occlusion as the result of the interaction of many factors, rather than a single molecular measurement, she says.

To show that this device could be useful for drug development, the researchers also tested a potential sickle cell disease drug called 5-hydroxymethyl furfural, which improves hemoglobin’s ability to bind to oxygen. Adding the drug to blood, they found, dramatically improved how it flowed through the device.

Franklin Bunn, director of hematology research at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, who was not part of this study, says the device could prove very helpful for drug development. “It provides an objective way of assessing new drugs that hopefully will continue to be developed to inhibit the sickling of red blood cells,” Bunn says.

The researchers have applied for a patent on the technology and are now working on developing it as a diagnostic and research tool.

New technology may help doctors predict when patients are at risk for serious complications.

Publication Date:

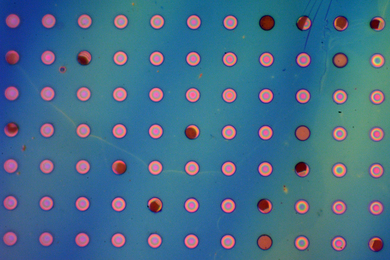

Caption:

Researchers from MIT, Harvard, MGH and Brigham and Women's Hospital have developed a microfluidic device that can analyze the behavior of blood samples from sickle cell disease patients, which usually include many crescent-shaped cells.

Credits:

Image: NIH