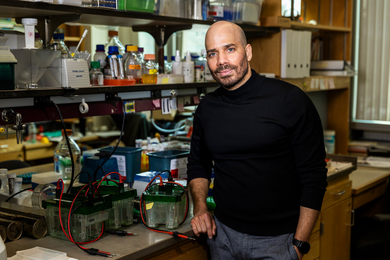

When patients awaken from surgery, they’re usually groggy and disoriented; it can take hours for a patient to become fully clearheaded again. Emery Brown, an MIT neuroscientist and an anesthesiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), thinks it doesn’t have to be that way.

Brown and colleagues at MGH are studying the effects of stimulants that could be used to bring patients out of general anesthesia much faster. One potential candidate is Ritalin, the drug commonly used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). In a study published online Sept. 20 in the journal Anesthesiology, the researchers show that giving anesthetized rats an injection of Ritalin brings them out of anesthesia almost immediately.

“It’s like giving a shot of adrenaline to the brain,” says Brown, who is a professor in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and the Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology. His co-authors on the study are lead author Ken Solt, Joseph Cotten, Aylin Cimenser, Kevin Wong and Jessica Chemali.

If replicated in humans, the findings could lead to new approaches that allow patients to regain lucidity in a matter of minutes rather than hours, Brown says.

Long recovery

Currently, there are no drugs to bring people out of anesthesia. When surgeons finish an operation, the anesthesiologist turns off the drugs that put the patient under and waits for them to wake up and regain the ability to breathe on their own. This usually takes five to 10 minutes; patients are often bleary for at least an hour or two afterward.

There are many reasons why it would be beneficial to bring patients out of anesthesia more quickly, Brown says. For one, many surgical patients want to be able to get back to a clearheaded state that allows them to make important decisions soon after their operations.

“Our thought is you should try to do things to clear up your head as quickly as possible,” Brown says. “The objective should be the return, as soon as possible, to the level at which the patient was before the operation.”

Bringing people to alertness more quickly could also cut down on health care costs, Brown says. At MGH, an hour of time in the operating room costs $1,000 to $1,500. With about 30,000 operations per year, an extra 10-minute stay for even a fraction of those patients adds up quickly.

“We’re all very cost-conscious now. It’s just the reality,” Brown says. “If I can give you a drug which is safe and it helps your brain restore its function after general anesthesia, let’s assume that’s a good thing. If, in addition, it means that you’re able to leave the operating room sooner, then that means the operating room flow can be just that much more efficient.”

Waking up the brain

In the Anesthesiology study, anesthetized rats that were given Ritalin came to in an average of 90 seconds. Rats who did not receive Ritalin took 280 seconds to revive.

When Ritalin enters the brain, it increases the amount of dopamine available in the brain’s cortex. In ADHD patients, this improves focus and attention; likewise, in the anesthetized brain, it appears to “wake up” areas of the cortex required for attention and decision making.

Brown and his colleagues are now seeking approval to run a clinical study at MGH. Because Ritalin has been used to treat ADHD since the 1960s, they believe it could earn FDA approval for this use more quickly than a brand-new drug.

“There is a need for drugs that reverse anesthesia,” says Zheng Xie, assistant professor of anesthesia at the University of Chicago, adding that this study represents a “significant finding.” Xie, who was not involved in the study, says that Ritalin is a good candidate, and that it might also be possible to design drugs that act in similar fashion without the potential side effects that some patients experience with the drug, such as hypertension, hyperventilation and nausea.

The dosage that would be needed to wake up an anesthetized human is not yet determined, but Brown says it would be “well within the doses that people would normally tolerate.”

Brown is also interested in studying whether stimulant drugs might be beneficial in efforts to revive comatose patients.

Brown and colleagues at MGH are studying the effects of stimulants that could be used to bring patients out of general anesthesia much faster. One potential candidate is Ritalin, the drug commonly used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). In a study published online Sept. 20 in the journal Anesthesiology, the researchers show that giving anesthetized rats an injection of Ritalin brings them out of anesthesia almost immediately.

“It’s like giving a shot of adrenaline to the brain,” says Brown, who is a professor in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and the Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology. His co-authors on the study are lead author Ken Solt, Joseph Cotten, Aylin Cimenser, Kevin Wong and Jessica Chemali.

If replicated in humans, the findings could lead to new approaches that allow patients to regain lucidity in a matter of minutes rather than hours, Brown says.

Long recovery

Currently, there are no drugs to bring people out of anesthesia. When surgeons finish an operation, the anesthesiologist turns off the drugs that put the patient under and waits for them to wake up and regain the ability to breathe on their own. This usually takes five to 10 minutes; patients are often bleary for at least an hour or two afterward.

There are many reasons why it would be beneficial to bring patients out of anesthesia more quickly, Brown says. For one, many surgical patients want to be able to get back to a clearheaded state that allows them to make important decisions soon after their operations.

“Our thought is you should try to do things to clear up your head as quickly as possible,” Brown says. “The objective should be the return, as soon as possible, to the level at which the patient was before the operation.”

Bringing people to alertness more quickly could also cut down on health care costs, Brown says. At MGH, an hour of time in the operating room costs $1,000 to $1,500. With about 30,000 operations per year, an extra 10-minute stay for even a fraction of those patients adds up quickly.

“We’re all very cost-conscious now. It’s just the reality,” Brown says. “If I can give you a drug which is safe and it helps your brain restore its function after general anesthesia, let’s assume that’s a good thing. If, in addition, it means that you’re able to leave the operating room sooner, then that means the operating room flow can be just that much more efficient.”

Waking up the brain

In the Anesthesiology study, anesthetized rats that were given Ritalin came to in an average of 90 seconds. Rats who did not receive Ritalin took 280 seconds to revive.

When Ritalin enters the brain, it increases the amount of dopamine available in the brain’s cortex. In ADHD patients, this improves focus and attention; likewise, in the anesthetized brain, it appears to “wake up” areas of the cortex required for attention and decision making.

Brown and his colleagues are now seeking approval to run a clinical study at MGH. Because Ritalin has been used to treat ADHD since the 1960s, they believe it could earn FDA approval for this use more quickly than a brand-new drug.

“There is a need for drugs that reverse anesthesia,” says Zheng Xie, assistant professor of anesthesia at the University of Chicago, adding that this study represents a “significant finding.” Xie, who was not involved in the study, says that Ritalin is a good candidate, and that it might also be possible to design drugs that act in similar fashion without the potential side effects that some patients experience with the drug, such as hypertension, hyperventilation and nausea.

The dosage that would be needed to wake up an anesthetized human is not yet determined, but Brown says it would be “well within the doses that people would normally tolerate.”

Brown is also interested in studying whether stimulant drugs might be beneficial in efforts to revive comatose patients.