Some of the subtleties of language can be challenging to explain using traditional linguistic analysis. Associate Professor Martin Hackl’s experimental approach is expanding the field of linguistics.

Take, for example, the subtle difference between "most" and "more than half." Native speakers of English will agree that there is a subtle difference between “most” and “more than half,” even though the root meanings are equivalent. Yet, until recently, linguists have categorized the two expressions the same way. Meaning is what matters, according to standard semantic theory — not form.

But that wasn’t good enough for the newest member of the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Science's Linguistics faculty, Associate Professor Martin Hackl. A specialist in syntax and semantics, Hackl is interested in how meaning comes about, why one sentence is acceptable in a particular context while others fail to communicate. In particular, he endeavors to understand quantifiers — words such as “every,” “most” and “more than.”

Traditional semantic analysis, which is based on logic, has trouble explaining these terms. Typical semantic studies, which involve asking speakers’ intuitions about what entailment a word or an expression is associated with, also fail to adequately explain whether “most” is completely interchangeable with “more than half.”

Ingenious research

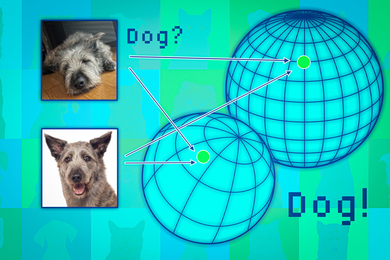

So, Hackl took a new approach: with support from the National Science Foundation, he created a lab experiment. Using a computer program, he showed subjects various arrays of dots, which are uncovered in a step by step fashion rather than being revealed all at once, and asked them to identify whether “most” of the dots were blue, or whether “more than half” were blue. The computer kept track of how long it took people to absorb each piece of newly uncovered information, and the difference was measurable. Answering questions involving “more than half” always took longer.

The implication is that linguistic form affects human understanding and behavior at a level that previous theories have not fully recognized. Now, Hackl is working on ways to enrich the descriptive machinery available to linguists in order to deal with “most.”

A search for a system

“You need a formal system to analyze things like ‘most’ that goes beyond predicate logic — but not so much beyond that you lose the ability to distinguish between expressions like 'most' and 'more than half,'” Hackl said. “My effort is to find a system that does that.”

Take, for example, the subtle difference between "most" and "more than half." Native speakers of English will agree that there is a subtle difference between “most” and “more than half,” even though the root meanings are equivalent. Yet, until recently, linguists have categorized the two expressions the same way. Meaning is what matters, according to standard semantic theory — not form.

But that wasn’t good enough for the newest member of the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Science's Linguistics faculty, Associate Professor Martin Hackl. A specialist in syntax and semantics, Hackl is interested in how meaning comes about, why one sentence is acceptable in a particular context while others fail to communicate. In particular, he endeavors to understand quantifiers — words such as “every,” “most” and “more than.”

Traditional semantic analysis, which is based on logic, has trouble explaining these terms. Typical semantic studies, which involve asking speakers’ intuitions about what entailment a word or an expression is associated with, also fail to adequately explain whether “most” is completely interchangeable with “more than half.”

Ingenious research

So, Hackl took a new approach: with support from the National Science Foundation, he created a lab experiment. Using a computer program, he showed subjects various arrays of dots, which are uncovered in a step by step fashion rather than being revealed all at once, and asked them to identify whether “most” of the dots were blue, or whether “more than half” were blue. The computer kept track of how long it took people to absorb each piece of newly uncovered information, and the difference was measurable. Answering questions involving “more than half” always took longer.

The implication is that linguistic form affects human understanding and behavior at a level that previous theories have not fully recognized. Now, Hackl is working on ways to enrich the descriptive machinery available to linguists in order to deal with “most.”

A search for a system

“You need a formal system to analyze things like ‘most’ that goes beyond predicate logic — but not so much beyond that you lose the ability to distinguish between expressions like 'most' and 'more than half,'” Hackl said. “My effort is to find a system that does that.”