Below is the prepared text of the Commencement address by Raymond S. Stata ’57, chairman and cofounder of Analog Devices Inc., for MIT's 144th Commencement held June 4, 2010.

Good morning and congratulations. You should be brimming with pride this morning. You earned a degree from the world’s most prestigious university focused on science and engineering. You mastered MIT’s unique brand of learning and doing which will distinguish you throughout your career. Congratulations as well to your family and friends who supported you and encouraged you along the way.

Your satisfaction and happiness in life depend on the choices you make and on the principles and values which guide them. So far your choices have served you extremely well. As a fellow nerd, I am honored to share with you some of my experiences and some of the principles and values that have worked well for me.

As MIT graduates we are all innovators and entrepreneurs at heart. We search for opportunities to do things better, to make things happen and to change the world.

In my case, I also had a strong desire to be in control of my destiny. So to satisfy this need I aspired to someday start my own company. With this end in mind, shortly after graduation I went to work for Hewlett Packard. Hewlett Packard was for me like a mini MBA where I learned the basics of business. But more importantly I learned from Hewlett Packard that commitment to the welfare of employees and to the development of their full potential are the cornerstones on which successful businesses are built.

You sometimes don’t know where the path you take will lead. When I was about 27, one day in Harvard Square, I bumped into Matthew Lorber, an acquaintance from my student days. Matt was looking for a roomate; we ended up not only sharing an apartment, but also together three years later we founded Analog Devices. Of course, we had no idea that Analog Devices would become a multi-billion dollar company and a leader in an important segment of the semiconductor industry. We started by carving out a small niche and then step by step we extended our core competencies and built on our success.

Analog’s business strategy focused on opportunities where we could achieve and sustain leadership. Our mantra was “Market Leadership through Technical Innovation.” Being number one not only produces superior business results, it also engenders a sense of pride and satisfaction and stimulates your competitive instincts to stay ahead. Don’t ever give up your ambition to be the best at whatever you do. It’s much more rewarding — and it’s also more fun.

We quickly discovered that you can’t be an innovative company unless you have great innovators. So at Analog, rather than “sidetracking” our best engineers into management, we created a parallel ladder to encourage them to continue their technical careers. We not only provided compensation that was comparable to the management track, but we also gave engineers a voice in influencing business strategy, investment decisions, organization policies; I encouraged managers to treat engineers as full business partners.

The highest rung on our technical ladder was reserved for our most distinguished engineers, who we called Analog Devices Fellows. Fellows at Analog are important people whose views are respected and valued. Don’t let organization hierarchy obscure the people who are most important to your success.

Another important way to unlock innovation is to free people to do their best work. In building the organization I found that a lot of talented people were just like me. They wanted the freedom to decide what to do and how to do it. So I shaped a culture which gave employees broad latitude to make decisions. We didn’t have a lot of rules and controls. We depended more on developing people’s judgment. We aligned the goals of the company and the goals of employees, and we encouraged employees to think about the company’s success as a prerequisite to their own. Empowering people to make decisions and to take ownership is a powerful motivator. This was a key factor in our success.

In effect, we built our market position on a culture of innovation. But then the question becomes — how do you maintain your lead? Andy Grove, the former CEO of Intel, wrote a book in which he proclaimed, “only the paranoid survive.” Beware of S-Curve’s because everything has life cycles — technologies, products, markets and companies. To sustain innovation, you can’t abandon your appetite for risk.

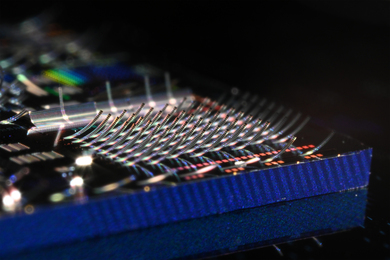

When we started Analog Devices, linear integrated circuits or so-called IC’s had not yet been invented. We manufactured operational amplifiers and converters by manually assembling discreet transistors and other components on printed circuit boards.

Just two years after we opened our doors, the industry’s first integrated circuit operational amplifiers were introduced. Our hand-tweaked amplifiers consistently outperformed these new devices — but each year they got better, and they were an order of magnitude cheaper. I concluded that — to avoid becoming victims of our own S-curve — we had to take bold steps to learn how to design and manufacture IC’s, or our success would be short lived.

Everyone in the company disagreed. They said that integrated circuits would never meet our customer’s performance requirements, that we shouldn’t risk a rapidly growing, profitable business, that we didn’t have the financial resources to compete with the large semiconductor companies and besides no one in the company knew anything about semiconductor technology. So the board said no. It was too risky.

For me the risk of inaction was even greater, so I made an offer the board couldn’t refuse. I offered to personally fund a startup company to design and manufacture IC’s which Analog Devices would sell. If the venture succeeded, ADI would have an option to acquire the company with no gain for my investment.

If it failed I would personally suffer the loss. People thought I was foolish, but it worked. Three years later, Analog Devices acquired the startup and got serious about semiconductor technology.

We figured out ways to manufacture IC’s that achieved performance even better than our hand assembled products, at a fraction of the cost. This breakthrough innovation established ADI as the industry leader in high performance linear integrated circuits, a position we still hold today.

The point is, entrepreneurs have to be optimistic and relentless in believing they will discover or create the missing pieces even when they are not sure how. Courage and the capacity to take risk are fundamental to entrepreneurship. If you are not stepping outside your comfort zone to take calculated risks, chances are you will not be exploiting your full potential. You can’t play it safe and win.

Don’t be afraid to fail or make mistakes — odds are you will many times. Failure is not always bad. In fact people don’t learn by doing things right. They learn by making mistakes and then reflecting on what went wrong.

My wife Maria says that I am frequently wrong but never in doubt. Well, I’m not too sure about the frequently part but I have surely made my share of mistakes. Perhaps my biggest failure was Analog Devices Enterprises, a venture investment fund I setup within the company.

Nothing came of it, and we lost a lot of money. My mistake was to allow our investments to stray too far from Analog’s core competencies. In the delicate balance between focus and diversification, I stepped over the line — but we certainly learned from it.

But if success for an entrepreneur depends on cultivating perpetual innovation, it also depends on how you work with others, how much you demand of yourself — and how much you believe in what you’re doing.

For most of you, your accomplishments will be magnified by productive collaborations, and by your ability to lead teams and organizations. To those ends, I’ve found you can be most effective by building trustful relationships. You earn trust through honesty, adhering to the facts; integrity living by principles; sincerity, meaning what you say; reliability, meeting your commitments; and competence, knowing what you are doing.

As high achievers in the real world you will soon discover as I did that you can’t substitute working smarter for working harder. To excel at the top of your game you have to do both. So be prepared to continue to drink from the fire hose as a way of life.

The most important advice I can give you is this: if ever you find that you are not passionate and excited about what you are doing, then start searching for an opportunity where you will be. Nothing is more important and gratifying than getting up in the morning with an eagerness to get to work and accomplish something important. Set high standards for what you expect from your work, be courageous in stepping into the unknown and think big about what you can accomplish.

If history is any guide, as MIT graduates 40 percent of you will have played an important role in an early stage startup venture by the time you reach age forty-five. A recent Sloan School study reported that cumulatively, 122,000 living MIT graduates have founded more than 25,000 companies which are still in business today and which collectively generate $2 trillion in revenues and 3.3 million jobs. And this does not include the companies that were acquired.

And the fact is that the spirit of innovation and entrepreneurship applies not just to business, engineering and science, but to every aspect of work and life. You are all well equipped to challenge the status quo and to bring about dramatic changes and improvements in whatever you choose to do. And you will also find opportunities as volunteers to apply your knowledge and skills to solve important societal problems.

From my involvement in K through 12 education, I’ve found that public institutions are the ones most in need of intervention from iconoclasts like us to engineer desperately needed change and improvements.

MIT has played a very important role in my life. As a “hay-seed” from a small farm community, I was the first in my family to attend college. Without MIT’s need blind admissions I would not have had access to the Institute’s unique education experience. As soon as we could afford it, Maria and I made a gift to not only repay MIT for the significant investment it made in me, but also to repay a debt of gratitude for what MIT had enabled me to do in my career.

Beyond what I gained personally, as I became more involved I came to better understand MIT’s enormous impact on the world — an impact that I’m convinced will become even more important in this complicated century. With its unmatched depth and breadth of research, and its culture of interdisciplinary collaboration, MIT is uniquely positioned to tackle the world’s biggest problems — energy, climate change, poverty and the diagnosis and care of disease. Maria and I believe so strongly in that mission — and in the people of MIT — that we have actively looked for ways to help MIT do what it does best.

For example, as a member of the Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Visiting Committee, I learned there was an urgent need to better integrate these disciplines by relocating the Computer Science side of the department from across the tracks in Tech Square to campus. So Maria and I offered to make a lead gift to catalyze this important decision. Initially the new facility was conceived as just another box on Vassar Street. But once started, the imagination of the faculty and Institute leaders was unleashed and the project took on a bolder vision than just a new home for computer science.

It quickly became an inspiring space for students and faculty from across the campus to play, hang out, eat, exercise and even dance — a space to facilitate human interaction and to germinate new ideas. The Center stands today as a constant reminder that MIT is about breaking with tradition and exploring new frontiers.

There are many, many examples, large and small, where MIT graduates got involved, saw a need and became part of the solution.

I urge you to stay involved with MIT, to search for ways where you can make a difference and when your time comes, to give back. Like its peer universities, MIT very much depends on the work, wisdom and wealth of its graduates to sustain its greatness. Equally important, as the products of MIT’s education, it is through your accomplishments that MIT’s contributions to society are amplified.

You are entering a troubled world that is both in crisis and in transition; In crisis due to the lapse of judgment and moral values of business and political leaders which triggered a deep and far reaching financial meltdown; in transition due to China, Russia and India ending decades of isolation and releasing 3 billion people into the free market economy. Coping with the stresses on financial and natural resources from an aging and growing global population with increasing expectations for a better life, presents seemingly insurmountable challenges. But when I reflect on the ingenuity of the human race and on the truly amazing things which have been accomplished just in my lifetime, I’m optimistic that your generation will not only find solutions to today’s challenges but you will also discover new opportunities for progress in a more integrated and inclusive world.

Remember, as MIT graduates you are the best the world has to offer. With technology playing an ever-increasing role, you have a special responsibility to help create a future where every person on the planet can have the hope and the prospects for a better life. My charge to you this morning is don’t play it safe — because the risk of inaction is too great. Dare to be part of the solution.

Good morning and congratulations. You should be brimming with pride this morning. You earned a degree from the world’s most prestigious university focused on science and engineering. You mastered MIT’s unique brand of learning and doing which will distinguish you throughout your career. Congratulations as well to your family and friends who supported you and encouraged you along the way.

Your satisfaction and happiness in life depend on the choices you make and on the principles and values which guide them. So far your choices have served you extremely well. As a fellow nerd, I am honored to share with you some of my experiences and some of the principles and values that have worked well for me.

As MIT graduates we are all innovators and entrepreneurs at heart. We search for opportunities to do things better, to make things happen and to change the world.

In my case, I also had a strong desire to be in control of my destiny. So to satisfy this need I aspired to someday start my own company. With this end in mind, shortly after graduation I went to work for Hewlett Packard. Hewlett Packard was for me like a mini MBA where I learned the basics of business. But more importantly I learned from Hewlett Packard that commitment to the welfare of employees and to the development of their full potential are the cornerstones on which successful businesses are built.

You sometimes don’t know where the path you take will lead. When I was about 27, one day in Harvard Square, I bumped into Matthew Lorber, an acquaintance from my student days. Matt was looking for a roomate; we ended up not only sharing an apartment, but also together three years later we founded Analog Devices. Of course, we had no idea that Analog Devices would become a multi-billion dollar company and a leader in an important segment of the semiconductor industry. We started by carving out a small niche and then step by step we extended our core competencies and built on our success.

Analog’s business strategy focused on opportunities where we could achieve and sustain leadership. Our mantra was “Market Leadership through Technical Innovation.” Being number one not only produces superior business results, it also engenders a sense of pride and satisfaction and stimulates your competitive instincts to stay ahead. Don’t ever give up your ambition to be the best at whatever you do. It’s much more rewarding — and it’s also more fun.

We quickly discovered that you can’t be an innovative company unless you have great innovators. So at Analog, rather than “sidetracking” our best engineers into management, we created a parallel ladder to encourage them to continue their technical careers. We not only provided compensation that was comparable to the management track, but we also gave engineers a voice in influencing business strategy, investment decisions, organization policies; I encouraged managers to treat engineers as full business partners.

The highest rung on our technical ladder was reserved for our most distinguished engineers, who we called Analog Devices Fellows. Fellows at Analog are important people whose views are respected and valued. Don’t let organization hierarchy obscure the people who are most important to your success.

Another important way to unlock innovation is to free people to do their best work. In building the organization I found that a lot of talented people were just like me. They wanted the freedom to decide what to do and how to do it. So I shaped a culture which gave employees broad latitude to make decisions. We didn’t have a lot of rules and controls. We depended more on developing people’s judgment. We aligned the goals of the company and the goals of employees, and we encouraged employees to think about the company’s success as a prerequisite to their own. Empowering people to make decisions and to take ownership is a powerful motivator. This was a key factor in our success.

In effect, we built our market position on a culture of innovation. But then the question becomes — how do you maintain your lead? Andy Grove, the former CEO of Intel, wrote a book in which he proclaimed, “only the paranoid survive.” Beware of S-Curve’s because everything has life cycles — technologies, products, markets and companies. To sustain innovation, you can’t abandon your appetite for risk.

When we started Analog Devices, linear integrated circuits or so-called IC’s had not yet been invented. We manufactured operational amplifiers and converters by manually assembling discreet transistors and other components on printed circuit boards.

Just two years after we opened our doors, the industry’s first integrated circuit operational amplifiers were introduced. Our hand-tweaked amplifiers consistently outperformed these new devices — but each year they got better, and they were an order of magnitude cheaper. I concluded that — to avoid becoming victims of our own S-curve — we had to take bold steps to learn how to design and manufacture IC’s, or our success would be short lived.

Everyone in the company disagreed. They said that integrated circuits would never meet our customer’s performance requirements, that we shouldn’t risk a rapidly growing, profitable business, that we didn’t have the financial resources to compete with the large semiconductor companies and besides no one in the company knew anything about semiconductor technology. So the board said no. It was too risky.

For me the risk of inaction was even greater, so I made an offer the board couldn’t refuse. I offered to personally fund a startup company to design and manufacture IC’s which Analog Devices would sell. If the venture succeeded, ADI would have an option to acquire the company with no gain for my investment.

If it failed I would personally suffer the loss. People thought I was foolish, but it worked. Three years later, Analog Devices acquired the startup and got serious about semiconductor technology.

We figured out ways to manufacture IC’s that achieved performance even better than our hand assembled products, at a fraction of the cost. This breakthrough innovation established ADI as the industry leader in high performance linear integrated circuits, a position we still hold today.

The point is, entrepreneurs have to be optimistic and relentless in believing they will discover or create the missing pieces even when they are not sure how. Courage and the capacity to take risk are fundamental to entrepreneurship. If you are not stepping outside your comfort zone to take calculated risks, chances are you will not be exploiting your full potential. You can’t play it safe and win.

Don’t be afraid to fail or make mistakes — odds are you will many times. Failure is not always bad. In fact people don’t learn by doing things right. They learn by making mistakes and then reflecting on what went wrong.

My wife Maria says that I am frequently wrong but never in doubt. Well, I’m not too sure about the frequently part but I have surely made my share of mistakes. Perhaps my biggest failure was Analog Devices Enterprises, a venture investment fund I setup within the company.

Nothing came of it, and we lost a lot of money. My mistake was to allow our investments to stray too far from Analog’s core competencies. In the delicate balance between focus and diversification, I stepped over the line — but we certainly learned from it.

But if success for an entrepreneur depends on cultivating perpetual innovation, it also depends on how you work with others, how much you demand of yourself — and how much you believe in what you’re doing.

For most of you, your accomplishments will be magnified by productive collaborations, and by your ability to lead teams and organizations. To those ends, I’ve found you can be most effective by building trustful relationships. You earn trust through honesty, adhering to the facts; integrity living by principles; sincerity, meaning what you say; reliability, meeting your commitments; and competence, knowing what you are doing.

As high achievers in the real world you will soon discover as I did that you can’t substitute working smarter for working harder. To excel at the top of your game you have to do both. So be prepared to continue to drink from the fire hose as a way of life.

The most important advice I can give you is this: if ever you find that you are not passionate and excited about what you are doing, then start searching for an opportunity where you will be. Nothing is more important and gratifying than getting up in the morning with an eagerness to get to work and accomplish something important. Set high standards for what you expect from your work, be courageous in stepping into the unknown and think big about what you can accomplish.

If history is any guide, as MIT graduates 40 percent of you will have played an important role in an early stage startup venture by the time you reach age forty-five. A recent Sloan School study reported that cumulatively, 122,000 living MIT graduates have founded more than 25,000 companies which are still in business today and which collectively generate $2 trillion in revenues and 3.3 million jobs. And this does not include the companies that were acquired.

And the fact is that the spirit of innovation and entrepreneurship applies not just to business, engineering and science, but to every aspect of work and life. You are all well equipped to challenge the status quo and to bring about dramatic changes and improvements in whatever you choose to do. And you will also find opportunities as volunteers to apply your knowledge and skills to solve important societal problems.

From my involvement in K through 12 education, I’ve found that public institutions are the ones most in need of intervention from iconoclasts like us to engineer desperately needed change and improvements.

MIT has played a very important role in my life. As a “hay-seed” from a small farm community, I was the first in my family to attend college. Without MIT’s need blind admissions I would not have had access to the Institute’s unique education experience. As soon as we could afford it, Maria and I made a gift to not only repay MIT for the significant investment it made in me, but also to repay a debt of gratitude for what MIT had enabled me to do in my career.

Beyond what I gained personally, as I became more involved I came to better understand MIT’s enormous impact on the world — an impact that I’m convinced will become even more important in this complicated century. With its unmatched depth and breadth of research, and its culture of interdisciplinary collaboration, MIT is uniquely positioned to tackle the world’s biggest problems — energy, climate change, poverty and the diagnosis and care of disease. Maria and I believe so strongly in that mission — and in the people of MIT — that we have actively looked for ways to help MIT do what it does best.

For example, as a member of the Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Visiting Committee, I learned there was an urgent need to better integrate these disciplines by relocating the Computer Science side of the department from across the tracks in Tech Square to campus. So Maria and I offered to make a lead gift to catalyze this important decision. Initially the new facility was conceived as just another box on Vassar Street. But once started, the imagination of the faculty and Institute leaders was unleashed and the project took on a bolder vision than just a new home for computer science.

It quickly became an inspiring space for students and faculty from across the campus to play, hang out, eat, exercise and even dance — a space to facilitate human interaction and to germinate new ideas. The Center stands today as a constant reminder that MIT is about breaking with tradition and exploring new frontiers.

There are many, many examples, large and small, where MIT graduates got involved, saw a need and became part of the solution.

I urge you to stay involved with MIT, to search for ways where you can make a difference and when your time comes, to give back. Like its peer universities, MIT very much depends on the work, wisdom and wealth of its graduates to sustain its greatness. Equally important, as the products of MIT’s education, it is through your accomplishments that MIT’s contributions to society are amplified.

You are entering a troubled world that is both in crisis and in transition; In crisis due to the lapse of judgment and moral values of business and political leaders which triggered a deep and far reaching financial meltdown; in transition due to China, Russia and India ending decades of isolation and releasing 3 billion people into the free market economy. Coping with the stresses on financial and natural resources from an aging and growing global population with increasing expectations for a better life, presents seemingly insurmountable challenges. But when I reflect on the ingenuity of the human race and on the truly amazing things which have been accomplished just in my lifetime, I’m optimistic that your generation will not only find solutions to today’s challenges but you will also discover new opportunities for progress in a more integrated and inclusive world.

Remember, as MIT graduates you are the best the world has to offer. With technology playing an ever-increasing role, you have a special responsibility to help create a future where every person on the planet can have the hope and the prospects for a better life. My charge to you this morning is don’t play it safe — because the risk of inaction is too great. Dare to be part of the solution.