Engineers at MIT are developing a tiny sensor that could be used to detect minute quantities of hazardous gases, including toxic industrial chemicals and chemical warfare agents, much more quickly than current devices.

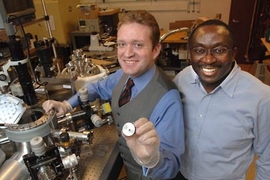

The researchers have taken the common techniques of gas chromatography and mass spectrometry and shrunk them to fit in a device the size of a computer mouse. Eventually, the team, led by MIT Professor Akintunde Ibitayo Akinwande, plans to build a detector about the size of a matchbox.

"Everything we're doing has been done on a macro scale. We are just scaling it down," said Akinwande, a professor of electrical engineering and computer science and member of MIT's Microsystems Technology Laboratories (MTL).

Akinwande and MIT research scientist Luis Velasquez-Garcia plan to present their work at the Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS) 2008 conference next week. In December, they presented at the International Electronic Devices Meeting.

Scaling down gas detectors makes them much easier to use in a real-world environment, where they could be dispersed in a building or outdoor area. Making the devices small also reduces the amount of power they consume and enhances their sensitivity to trace amounts of gases, Akinwande said.

He is leading an international team that includes scientists from the University of Cambridge, the University of Texas at Dallas, Clean Earth Technology and Raytheon, as well as MIT.

Their detector uses gas chromatography and mass spectrometry (GC-MS) to identify gas molecules by their telltale electronic signatures. Current versions of portable GC-MS machines, which take about 15 minutes to produce results, are around 40,000 cubic centimeters, about the size of a full paper grocery bag, and use 10,000 joules of energy.

The new, smaller version consumes about four joules and produces results in about four seconds.

The device, which the researchers plan to have completed within two years, could be used to help protect water supplies or for medical diagnostics, as well as to detect hazardous gases in the air.

The analyzer works by breaking gas molecules into ionized fragments, which can be detected by their specific charge (ratio of charge to molecular weight).

Gas molecules are broken apart either by stripping electrons off the molecules, or by bombarding them with electrons stripped from carbon nanotubes. The fragments are then sent through a long, narrow electric field. At the end of the field, the ions' charges are converted to voltage and measured by an electrometer, yielding the molecules' distinctive electronic signature.

Shrinking the device greatly reduces the energy needed to power it, in part because much of the energy is dedicated to creating a vacuum in the chamber where the electric field is located.

Another advantage of the small size is that smaller systems can be precisely built using microfabrication. Also, batch-fabrication will allow the detectors to be produced inexpensively.

The research, which started three years ago, is funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and the U.S. Army Soldier Systems Center in Natick, Mass.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on January 16, 2008 (download PDF).