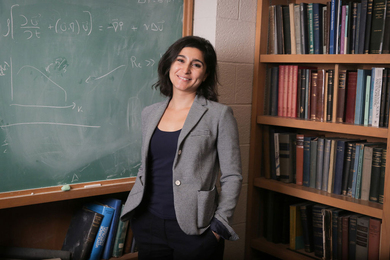

Kenneth Locke Hale, an MIT professor of linguistics known for his lifelong dedication to the study and preservation of endangered languages, died in his home in Lexington on Oct. 8. He was 67.

Hale, who came to MIT in 1967, was internationally renowned for his ability to quickly learn and communicate in dozens of languages.

Institute Professor Noam Chomsky, a colleague during the MIT years, responded "with inexpressible sadness and distress" to the news of Hale's death. "Ken Hale was a close and cherished friend for many years, a colleague whose contributions are incomparable and of immense intellectual distinction, and above all, a person of honor and courage who dedicated himself with passion and endless energy to protecting the rights of poor and suffering people throughout the world. One of the world's leading scholars, dear to countless people, he was also one of those very few people who truly merits the term 'a voice for the voiceless.' The loss is immeasurable," Chomsky said.

Throughout his career, Hale sought to obtain training in linguistics for the native speakers of indigenous languages. He felt that the study and preservation of native languages should be conducted by members of the affected culture, in addition to outsiders. Two of his graduate students at MIT--Paul R. Platero, a Navajo, and LaVerne Masayesva Jeanne, a Hopi--are believed to be the first Native Americans to receive doctorates in linguistics.

In a paper titled "The Human Value of Local Languages," Hale wrote, "The loss of local languages and of the cultural systems which they express has meant irretrievable loss of diverse and interesting intellectual wealth. Only with diversity can it be guaranteed that all avenues of human intellectual progress will be traveled."

In an interview in 1995, Hale said "When you lose a language, a large part of the culture goes, too, because much of that culture is encoded in the language."

"Ken viewed languages as if they were works of art. Every person who spoke a language was a curator of a masterpiece," said Samuel Jay Keyser, professor emeritus of linguistics and a close friend and colleague of Hale for more than 20 years. Keyser noted that Hale was one of the most significant linguists in the world and also a man of grace and humility who believed that speaking to a person in his or her own language was above all, an act of courtesy.

"Many people have that ability to gain near-native command of language, but few have Ken Hale's theoretical imagination. I was constantly mesmerized by his creativity," Keyser said.

Philip S. Khoury, dean of the School of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, recalled Hale's expertise and good humor. "Ken Hale was a giant in linguistics and a great, compassionate human being. He had the ability to learn and speak languages by the dozens and he did. Once I asked him about this, and he said, 'The problem is that many of the languages I've learned are extinct or close to extinction, and I have no one to speak them with!'" Khoury said.

THEORETICAL INTERESTS

Hale's theoretical interests focused on the cross-linguistic study of language universals--he studied as many structurally diverse languages as possible in order to discover laws governing them all.

Professor of Linguistics Sabine Iatridou, an MIT colleague and a former student of Hale, explained, "The idea is that if a particular phenomenon holds in a variety of languages, chances are it is reflection of what is called universal grammar--the properties of human language proper, not a result of accidental or historical reasons. A lot of theoretical linguistics relies on finding generalizations that hold across languages that are genetically unrelated."

Over the course of his disciplined and devoted career, Hale contributed significantly to the development of a general theory of the human capacity for language, his colleagues agreed.

"Ken was the world's foremost cross-linguistic linguist. His knowledge of language and languages is legendary. So many of his hypotheses over the years had borne fruit--remarkable fruit, in fact," Iatridou said. "Many linguists working today do not realize how much of the theoretical background they are assuming had been initially proposed by Ken. However, beyond his immeasurable contributions to the field, which are easily quantifiable by looking at Ken's writings, his students and his overall influence, Ken's dedication and great part of his life's work was his love, care and help to people in need everywhere."

A NEW HOME ON THE RANGE

Following the sudden death of his grandfather when he was six, Hale's family moved from Chicago to a ranch in Canelo, Ariz, where his pursuits included trapping and gunsmithing. He attended grade school in a one-room schoolhouse that he reached on horseback each day.

Hale's interests in language blossomed in 1948, when he was sent to the Verde Valley School in Sedona, Ariz. There, according to Keyser, "Ken first roomed with a Hopi boy and learned Hopi, then with a boy from Jemez and learned Jemez. He had to figure out a way to write the languages since there was no writing system for them.

"I learned faster by working on more than one language at a time," Hale said according to Keyser, moving on quickly in Tucson High School to studying Navajo, O'odam, Pachuco, Polish and "whatever else came along."

With characteristic passion, Hale also enjoyed rodeo bull-riding. As an undergraduate at the University of Arizona, he divided his time between weekend "jackpot" rodeos and studying anthropology and Native American languages. In his senior year, he won the bull-riding event in the University of Arizona rodeo and wore the trophy belt buckle for the rest of his life.

Hale received the B.A. in anthropology from the University of Arizona in 1955, the M.A. in linguistics from Indiana University at Bloomington in 1956 and the Ph.D. in linguistics from Indiana in 1958. From 1958-61, Hale conducted research under an NSF grant on Australian aboriginal languages. Before coming to MIT, he taught at the University of Illinois at Urbana (1961-64) and the University of Arizona (1964-66). He also taught a course on Walpiri literacy for Walpiri-speaking teachers in the Yuendumu School in Central Australia in 1974 and a course on Navajo linguistics in Kinlichee, Ariz., in 1975.

Starting in 1985, Hale made many trips to the Atlantic coast of Nicaragua to mentor native linguists in four indigenous languages of the region. During the last five summers of his life, Hale taught for and served on the board of directors of the Navajo Language Academy. He also was actively involved with the language revitalization project of the Wampanoag tribe in New England.

Dr. Hale is survived by his wife, Sara Hale of Lexington; his brother, Stephen F. Hale of Tucson; and four sons: Whitaker of Arlington, Ian of Tucson, Caleb of Atlanta and Ezra of Lexington.

A memorial for Professor Hale will be held at MIT on Thursday, Nov. 1 at 2 p.m. in Wong Auditorium. Burial will be private.

Donations in Hale's memory may be sent to the Navajo Language Academy (attn: Peggy Speas, treasurer) Department of Linguistics, University of Massachusetts at Amherst, Amherst, MA, 01003.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on October 17, 2001.