History packed a lot into Building 20's rambling, peeling, barracks-like confines -- from lofty hopes to gritty heroics to the seeds of scientific revolution. And now, as the 55-year-old structure is about to be cleared to make way for a new building and a new era, three members of the MIT community -- two UROP students and a professor emeritus of electrical engineering -- ponder the question of what to do with the stuff that dreams are made on.

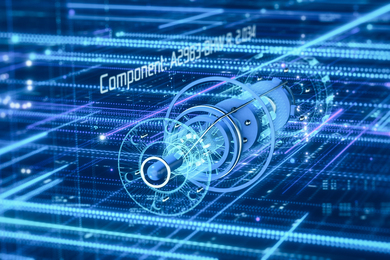

In true MIT style, the question became a problem and the problem became a set. A Building 20 time capsule, built to contain a variety of items and withstand a variety of conditions, was to be designed and ready for spring as a UROP project.

Tanisha Lloyd, a junior in mechanical engineering who aspires to be an inventor, took on designing the capsule itself.

"It was a project that would enable me to apply some of the design skills I learned from my mechanical engineering courses," she said. "I want the time capsule's design to reflect the history and achievements of Building 20. That was the home of radar, the UROP program, ROTC, the Acoustic Lab, the Council for the Arts and so much more. I want future students and faculty to get a sense of the history, not only by what is contained in the time capsule, but also from its exterior design," Ms. Lloyd said.

Previous MIT time capsules -- one was buried in Killian Court when President Vest was inaugurated -- stuck with the traditional chubby rocket style.

Ms. Lloyd's design for the Building 20 capsule has evolved from a miniature version of the structure's unevenly pronged fork shape to something less eccentric, she said.

"The first idea was to make the time capsule a scaled-down model of Building 20. However, a quick evaluation of building dimensions showed this was not a practical utilization of volume or space. The new design will incorporate the shape of Building 20 yet have a more practical box design that will enable better preservation of the enclosed material," she said.

The design group is looking into making the 4.2-cubic-foot rectangular capsule from stainless steel or oxidized aluminum. Weight, cost and manufacturing ease are the design criteria for material selection, said Ms. Lloyd. A model of Building 20 will sit on the "roof" of the box.

"None of us knew beans about time capsules," said Professor Francis Reintjes, who both guides the time capsule design project and is a member of the Building 20 commemoration committee, which will select the final design "It's something people get so emotional about. But, being engineers, we asked first, 'What's going inside?'"

Sonia Tulyani, a sophomore in chemical engineering, asked that question first as well. Her focus is on the actual stuff of dreams -- 55 years' worth -- that must be sealed and preserved so it can go inside Ms. Lloyd's practical, weatherproof box.

Items suggested for inclusion in the time capsule include a piece of Building 20 floorboard, a RadLab reunion book, a photo of the construction site in 1998, a list of major donors to the new complex, a coaster from the March 27th celebration, a poster of MIT's "Greatest Hacks," a sample of news media (year-end issues of Time and Newsweek), photos of famous MIT alumni/ae, a video of "Good Will Hunting," and instructions on how to deal, in 2053, with the 1998 electronic media contained in the box.

Photographs of Ms. Lloyd, Ms. Tulyani and Professor Reintjes will also be in the preservation mix.

Ms. Lloyd plans to do "the majority of the manufacturing of the time capsule with the aid and supervision of MIT's labs and technicians," she said.

The capsule, though designed for burial, will be kept in a glass case within the new facility for intelligence sciences. An electronic counter on the outside of the capsule will count down towards opening day, 55 years from now.

Both Ms. Lloyd and Ms. Tulyani have caught the spirit of the time capsule tradition despite their engineers' training. Both women will be about 70 when the capsule is opened, and they both hope to witness that event.

"I definitely want to be present when it is opened after 55 years. I can't imagine what MIT will be like, but it will be interesting to see," said Ms. Tulyani.

Ms. Lloyd looked into her own family's past and future life as she pondered the project.

"I participated in making a time capsule in first grade. I remember it was fun learning how to preserve items for years and years to come. In my own time capsule, I would probably put all of the stuff I would want my children and grandchildren to know about their heritage, what life was like when I was young, and my hopes and dreams for the future," she said.

A version of this article appeared in MIT Tech Talk on March 18, 1998.